Is there any such thing as a feminist romantic suspense novel? I've been pondering this question as I read more widely in this romance sub-genre. Like the Gothic novel of the 18th and early 19th century, which relies on the threat of violence against women for most of its dramatic oomph, the majority of romantic suspense books I've come across features a heroine who is threatened with grave physical danger, most often in the form of a powerful, menacing male. And most often, said heroine is saved from said physical danger by another scary, but at least on her side, human of the male persuasion. Not really a recipe for empowered womanhood, you say? I would have to concur.

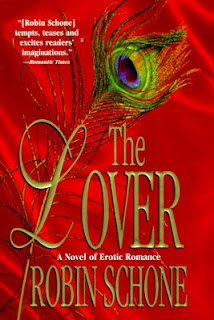

What happens, though, when an author bent on celebrating women's sexuality decides to take up the form? And pushes against the boundaries not only of romance fiction, but also of the Gothic? You get the creepy, compelling, yet deeply empowering book that served as one of the earliest examples of the erotic romance: Robin Schone's 1990's The Lover.

Thirty-six-year-old virgin spinster Anne Aimes has spent the majority of her adult life caring for the bodily needs of her elderly, ailing mother and father. Tired of fending off men who long for her parents' fortune, not her person, and no longer willing to be embarrassed by her own sexual needs after her parents are gone, Anne takes an unconventional, daring step: through her lawyer, she proposes a business arrangement with the most celebrated male prostitute in Europe, Michel des Anges. For ten thousand pounds, he will be her lover for a month, fulfilling her bodily needs and teaching her about the depths of sexual pleasure.

Michel agrees to Anne's proposal, but not for the money; his smoldering sexuality has already made him a fortune, not only in France, but now in England. No longer the beautiful young man Anne had once spied across a ballroom when she made her disastrous ton debut at eighteen, Michel (whose real name readers, but not Anne, are told right from novel's start, is really Michael) is now a scarred man; burned in a fire, his face and hands have sent women running in disgust, not moaning in passion, for the past five years. Yet his bodily scars do not even begin to hint at the emotional damage inflicted upon him by a sadistic figure in his past, a figure upon whom he plans revenge—by using Anne as bait.

Schone's narrative simultaneously depicts Anne's detailed, explicit, and deeply erotic introduction to sex while dropping more and more terrifying hints about the horrors of Michael's mysterious early life. Horrors so appalling that the thirteen-year-old runaway was only too glad to use the lessons of an enterprising madam to turn himself into a prostitute guaranteed to bring any woman to orgasm. For only by drowning himself in sex could Michael block out the sickening nightmares of his past.

In the typical romantic suspense, as in its predecessor the Gothic novel, as the plot grows ever closer to its end, so, too, does the threat to the female body. Yet despite the reader's growing awareness of the potential danger to

Anne, we're not all that worried about her. Not only because fairly early in their

relationship, Michael realizes he can no longer just use Anne as his

tool, and vows to keep her from harm, but also because the passion that

each draws out from the other is strikingly at odds with the subgenre's conventional conflation of physical danger with sexuality, particularly female sexuality.

In the typical romantic suspense, as in its predecessor the Gothic novel, as the plot grows ever closer to its end, so, too, does the threat to the female body. Yet despite the reader's growing awareness of the potential danger to

Anne, we're not all that worried about her. Not only because fairly early in their

relationship, Michael realizes he can no longer just use Anne as his

tool, and vows to keep her from harm, but also because the passion that

each draws out from the other is strikingly at odds with the subgenre's conventional conflation of physical danger with sexuality, particularly female sexuality.

In romantic suspense, threats to the heroine are often implicitly coded as sexual threats. In the earlier Gothic works, such threats were typically to the pure heroine's chastity (as in these covers from novels by the master of the Gothic, Ann Radcliffe, suggest); in more recent suspense, threats of rape or other sexual defilement. Schone, in contrast, works not only to identify this linkage between sexual passion and violation/death, but to break it.

But it is a terribly difficult linkage to break, given the society in which Anne and Michael live, a society that Schone claims in her introductory Author's Note is not all that different from our own. For in its casting of its villain, the novel suggests that this linkage lies at the very heart of patriarchy, and thus cannot be done in the typical romantic suspense way, with hero bravely protecting the heroine from all harm, or at least riding to her rescue before any real damage can be inflicted. It is only by understanding this that the reader can accept the ghastly turn that the novel takes in its final four chapters, a turn that leaves Anne at the mercy of Michael's tormentor, experiencing the same horrors that were once inflicted upon him, horrors intended to drive them into a disgust of every bodily desire.

Society punishes both men and women for their sexual desires, making them feel as if they are a horror, not a joy. But to reject passion because patriarchy would trick you into mistaking it for horror is the true tragedy, Schone's book asserts. Only by embracing her passion for Michael, in all its messy, bodily manifestations, can Anne learn to differentiate the screams of horror from the screams of passion, and break the damning linkage of desire and death.

|

| ...and afraid: the classic Gothic |

|

| Women in danger... |

Thirty-six-year-old virgin spinster Anne Aimes has spent the majority of her adult life caring for the bodily needs of her elderly, ailing mother and father. Tired of fending off men who long for her parents' fortune, not her person, and no longer willing to be embarrassed by her own sexual needs after her parents are gone, Anne takes an unconventional, daring step: through her lawyer, she proposes a business arrangement with the most celebrated male prostitute in Europe, Michel des Anges. For ten thousand pounds, he will be her lover for a month, fulfilling her bodily needs and teaching her about the depths of sexual pleasure.

Michel agrees to Anne's proposal, but not for the money; his smoldering sexuality has already made him a fortune, not only in France, but now in England. No longer the beautiful young man Anne had once spied across a ballroom when she made her disastrous ton debut at eighteen, Michel (whose real name readers, but not Anne, are told right from novel's start, is really Michael) is now a scarred man; burned in a fire, his face and hands have sent women running in disgust, not moaning in passion, for the past five years. Yet his bodily scars do not even begin to hint at the emotional damage inflicted upon him by a sadistic figure in his past, a figure upon whom he plans revenge—by using Anne as bait.

Schone's narrative simultaneously depicts Anne's detailed, explicit, and deeply erotic introduction to sex while dropping more and more terrifying hints about the horrors of Michael's mysterious early life. Horrors so appalling that the thirteen-year-old runaway was only too glad to use the lessons of an enterprising madam to turn himself into a prostitute guaranteed to bring any woman to orgasm. For only by drowning himself in sex could Michael block out the sickening nightmares of his past.

In the typical romantic suspense, as in its predecessor the Gothic novel, as the plot grows ever closer to its end, so, too, does the threat to the female body. Yet despite the reader's growing awareness of the potential danger to

Anne, we're not all that worried about her. Not only because fairly early in their

relationship, Michael realizes he can no longer just use Anne as his

tool, and vows to keep her from harm, but also because the passion that

each draws out from the other is strikingly at odds with the subgenre's conventional conflation of physical danger with sexuality, particularly female sexuality.

In the typical romantic suspense, as in its predecessor the Gothic novel, as the plot grows ever closer to its end, so, too, does the threat to the female body. Yet despite the reader's growing awareness of the potential danger to

Anne, we're not all that worried about her. Not only because fairly early in their

relationship, Michael realizes he can no longer just use Anne as his

tool, and vows to keep her from harm, but also because the passion that

each draws out from the other is strikingly at odds with the subgenre's conventional conflation of physical danger with sexuality, particularly female sexuality.In romantic suspense, threats to the heroine are often implicitly coded as sexual threats. In the earlier Gothic works, such threats were typically to the pure heroine's chastity (as in these covers from novels by the master of the Gothic, Ann Radcliffe, suggest); in more recent suspense, threats of rape or other sexual defilement. Schone, in contrast, works not only to identify this linkage between sexual passion and violation/death, but to break it.

But it is a terribly difficult linkage to break, given the society in which Anne and Michael live, a society that Schone claims in her introductory Author's Note is not all that different from our own. For in its casting of its villain, the novel suggests that this linkage lies at the very heart of patriarchy, and thus cannot be done in the typical romantic suspense way, with hero bravely protecting the heroine from all harm, or at least riding to her rescue before any real damage can be inflicted. It is only by understanding this that the reader can accept the ghastly turn that the novel takes in its final four chapters, a turn that leaves Anne at the mercy of Michael's tormentor, experiencing the same horrors that were once inflicted upon him, horrors intended to drive them into a disgust of every bodily desire.

Society punishes both men and women for their sexual desires, making them feel as if they are a horror, not a joy. But to reject passion because patriarchy would trick you into mistaking it for horror is the true tragedy, Schone's book asserts. Only by embracing her passion for Michael, in all its messy, bodily manifestations, can Anne learn to differentiate the screams of horror from the screams of passion, and break the damning linkage of desire and death.

Robin Schone, The Lover. Kensington, 2000.

Next time on RNFF

Be afraid, and carry a big pistol:

Romancing Gun Rights

"the majority of romantic suspense books I've come across features a heroine who is threatened with grave physical danger, most often in the form of a powerful, menacing male. And most often, said heroine is saved from said physical danger by another scary, but at least on her side, human of the male persuasion."

ReplyDeleteMary Stewart wrote romantic suspense novels in which the heroines save themselves/others.

Thanks for the reminder of Mary Stewart. Do you think it was easier to write feminist romantic suspense in the 60's and 70's than it is today?

ReplyDeleteI've no idea. How exactly does one define "romantic suspense" anyway? It occurs to me that perhaps one could think of some of Georgette Heyer's romances as "romantic suspense": The Talisman Ring, The Reluctant Widow, The Quiet Gentleman. And what about some of Jennifer Crusie's: Getting Rid of Bradley, What the Lady Wants, Tell Me Lies, Welcome to Temptation, Faking It.

DeleteBroadly, romantic suspense can be defined as a romance novel with a mystery to solve, or so says Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romance_novel#Romantic_suspense. Heyer's and Crusie's books would definitely qualify under this definition (although Crusie's use of comedy definitely complicates the genre boundaries, doesn't it?)

ReplyDeleteBut more specifically (or perhaps just more common?), romantic suspense seems to point to books in which the heroine is the victim target of criminal wrong-doing, and the hero plays some role in protecting her/saving her from the baddies. What interested me about Schone's book is its attempt to use or transform this latter, more specific type of romantic suspense in order to call its anti-feminist ideological underpinnings into question.

Would you place Stewart's work in the broader category, or in the more narrow one? I've not read her books myself -- yeah, another author to explore :-)

"Crusie's use of comedy definitely complicates the genre boundaries, doesn't it?"

DeleteThat's something she has in common with Heyer.

In Stewart's novels there's usually villainy afoot, and the heroine gets involved in trying to work out what's happened and stop the villain(s). Sometimes this puts her at risk. Often she collaborates with a hero, but usually she has to take decisive (and risky) action on her own. Nine Coaches Waiting is more Gothic, inasmuch as the heroine doesn't know whether the man she's falling in love with is a villain. She has to take action to protect a small boy.

I haven't read a lot of Suzanne Brockmann but the heroine of Harvard's Education is a spy/special agent and she definitely doesn't need to be protected. She and the hero get involved in military action, rather than a crime, so perhaps that's not exactly what you're looking for.

Oh, it just occurred to me that you might be interested in Kyra Kramer's "Raising Veils and other Bold Acts: The Heroine's Agency in Female Gothic Novels." Studies in Gothic Fiction 1.2 (2011), in which she discusses four romantic suspense novels by Elizabeth Lowell.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the rec, Laura. Glad to hear I'm not the only one seeing a relationship between romantic suspense and the Gothic. I'm looking forward to seeing what Kramer has to say about the two genres.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for your wonderful review of THE LOVER, Jackie. I was surprised ... and honored! ... that you chose THE LOVER. Not that I don't think it's worthy, but because I later wrote a series called THE MEN AND WOMEN'S CLUB (Scandalous Lovers, "The Men And Women's Club" [novella] and Cry For Passion) which is based upon a London group of men and women who met c1885-1889 to discuss sexual issues of the day, and who gave it their best to overcome male/female prejudisms of the day. I love exploring the social, moral and legal ramifications that women ... and men! ... suffered when they went against the traditional roles Victorian society assigned them. (Please forgive me if some of this doesn't sound quite right; I'm quickly piecing together what I lost when trying to post a few minutes ago).

ReplyDeleteLaura, I cut my reading teeth on Georgette Heyer and Mary Stewart. I remember well Nine Coaches Waiting. I think a lot of the Gothic Romance authors such as Mary Stewart, Phyllis Whitney and Victoria Holt espoused feminist theory. Their heroines were smart and independent. I'm proud to admit that I as an author was influenced by my love of Gothic Romance. :)

Robin Schone

Thanks for stopping by, Robin. THE LOVER is the first of your works that I've read, hence its appearance on the blog. I'm now looking forward to reading your entire oeuvre, especially your MEN AND WOMEN'S CLUB series!

ReplyDeleteI think one of the unique facets of Schone's work is the imperfection of sexuality in her books. Lots of romance IMO portray a perfect sexuality that morphs into the mechanical. I think Schone's work in THE LOVER and its sequel GABRIEL's WOMAN as well as the MEN AND WOMEN'S CLUB delve deeper into sexuality, including uncomfortable things like how childhood sexual abuse affects adult sexuality. Her books also have very nontraditional leads: aging women with saggy breasts and greying hair, a eunuch desiring human touch and many others that would never be cast as "normal" romance leads.

DeleteSchone's books may be erotic romance but they're not the glossy perfection erotic romance a la 50 Shades.

J9:

DeleteInteresting idea, that "ideal" sex can so easily morph into "mechanical," and hence boring, unimaginative, unconnected to and unable to evoke emotion. It reminds me of why I find so much visual/film pornography boring--it often strikes me as so repetitive, so scripted, so detached from any real people or any real emotion.

Books like Schone's (which I'm looking forward to reading more of, THE LOVER having been my first introduction to her work) that "delve deeper" into sexuality are rare, and well worth passing on the word about.

Thanks for stopping by, J9.

Can't wait to hear what you think about her other work.

DeleteThe Lovers sounds intriguing.

ReplyDeleteBy the Wikipedia definition, wouldn't J.D. Robb/Nora Robert's In Death series qualify as romantic suspense? Eve Dallas is a cop, but she doesn't generally rely on her love interest Roarke to save her. That might not be typical of romantic suspense, but the popularity of the In Death series suggests that a woman who primarily saves herself appeals to readers.

I've been meaning to borrow some of Whitney and Stewart's books from the library. I know I read at least one Whitney book when I was a teen; I'm not sure I've read anything of Stewart's outside of her Merlin trilogy. FWIW, I viewed the Whitney book I read as a mystery with romantic elements rather than as a romance.

Have to admit I haven't read any of the IN DEATH books; I have a sort of love/hate relationship with NR...

ReplyDeleteYes, I remember reading a Whitney or two as a teen, and a Victoria Holt, and not really liking the whole brooding Gothic mood. And yes, Whitney did seem more of a mystery than a romance. But I plan to give Stewart a try.

I've read one of the later In Death books and liked it, mostly. Mystery/detective novels are my genre of choice, but I've read pretty much everything there is in the genre that I'd like.

ReplyDeleteHave you read Gillian Flynn's thriller Gone Girl? The state of the main characters' marriage motivates everything that occurs in the book, but I'd describe it as more of an anti-romance.

It just occurred to me that Daphne DuMaurier's Rebecca is a female Gothic novel. I'm not sure it qualifies as romantic suspense, though; I don't recall an HEA.

What a great post, thanks for writing it...I write romantic suspense, and my goal is always to make the heroine as self-sufficient as possible while finding a way to let her and the hero need the other's support--it's not as easy as I thought it would be!

ReplyDeleteI've been a big fan of Robin Schone's writing for years. I never really analyzed why Schone, Brockmann and Crusie are my favorites, but now I think I get it!

Thanks, Teri Anne, for stopping by. Mutual support, yes, and mutual threat, too, I'm guessing is key to writing a feminist romantic suspense -- the feeling that not just the heroine, but the hero, too, is in real danger...

DeleteI love this post too--Tweeting it today. I don't read much in this genre, and I wonder if the gender issues are why. If the genres Historical, & Contemporary and the type of Paranormal I like do explore them explicitly, my experience of Romantic Suspense is like yours--it essentially relies on that same Damsel in Distress trope all too often. Thanks for the recommendation. I bought The Lover, even though it's only in paperback! Currently I have a thing about scarred heroes, and that set up sounds irresistible!

ReplyDeleteThanks, Amber, for stopping by, and for tweeting. Hope you enjoy THE LOVER!

DeleteGreat post, everyone, and wonderful to read all the comments.

ReplyDeleteMy issue is I have a hard time finding a Thriller with enough Romance to work for me, and also a Romance that's got enough Thriller to work for me. I want my heroine's strong - and smart enough to get out of harm's way, yet wise enough to feel the importance of love.

It's as if the two camps don't mix well. Perhaps these older Gothics are what I've been looking for to break that gender bias.

Thanks,

Paula

Glad you enjoyed the post, Paula, and especially the comments -- that's the best part of blogging, getting to participate in a larger conversation...

ReplyDeleteDoes "thriller" = "suspense" to you?

I've always thought of romantic suspense as being a little more progressive than other sub-genres. The characters are often evenly matched as far as power and socioeconomic status (vs. the duke and pauper, billionaire and secretary, Dom and sub etc). Most RS heroines have established careers. Many of the heroines work in law enforcement, in addition to or instead of the hero. Sure, there are damsels in distress, but not always. For me the appeal is in a protective hero and a strong heroine, who are both in danger and work together to get out.

ReplyDeleteJill:

ReplyDeleteThanks for stopping by. Do you have specific romantic suspense titles that you'd recommend as being "progressive"?

Hi Jackie,

ReplyDeleteNora Roberts writes strong heroines consistently in her single title RS books, not just the In Death series. Blue Smoke has a firefighter heroine who is sort of promiscuous. I'm a fan of Suzanne Brockmann's Troubleshooter series. Elle Kennedy and Maya Banks both have recent releases with assassin-type heroines. Linda Howard's Dying to Please has a bodyguard heroine.

I don't read as much RS as I used to (it feels like "my job") but my impression from blurbs and reviews is that most feature capable women, not helpless damsels. So I think you could pick up just about anything...good luck!

Thanks, Jill, for your recommendations. I think I assumed when I began reading romantic suspense that the "damsel in distress" trope would not be that common any more, and thus was surprised to find it still rearing its head in so many of the recent books. Or perhaps not rearing its head, but still lurking, hiding behind an image of empowered womanhood but simultaneously undercutting that same image (see the post on Howard and Jones's RUNNING WILD).

DeleteI'm looking forward to reading more widely, and hopefully discovering books that put both hero and heroine in danger, and allow both to contribute to saving each other.

I agree that the trope is common. I'm just not sure I agree that it undercuts the image of an empowered woman. The heroine in danger (distress) is an inherent part of the subgenre, and it's not empowering. Being unable to self-rescue is also not empowering, but not an essential piece of the RS puzzle.

DeleteWhen the hero is in danger, which is the case in all or most suspense, mystery and thriller novels, do we see that as not empowered? Only if he can't rescue himself. Often he's challenged by another man or men, so there is no gender inequality to question.

I can see the problem with the setup of a heroine in danger from a male villain, especially if another man rescues her. But most criminals are men, and writing female villains opens up another can of worms. I'm wondering how and if an RS author can alleviate the "in danger from man/men" issue. I can write a self-rescuing heroine, but not a female villain for every story. I'm not sure I understand what Schone did--no rescue at all?

I will come back and read the other post again, which might shed some light on this. Interesting discussion all around--thanks!

My sense of RS is similar to Jill Sorenson's, but I'm not widely enough read in it to offer an opinion of my own accord.

ReplyDeleteIn addition to the titles she mentioned, Mia Downing has a three-part series (Spy Games) of which the first two parts have been published so far that features BDSM and contains a m/f/m menage in the both first book and a side story set between the first and second books. Otherwise it's all het. The first novel has more suspense than the second one, but I liked both books very much.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteFWIW, I read Mary Stewart's Touch Not the Cat and loved it. The woman saved herself. Very feminist, in my view, even though set in the days when women were hotel receptionists (her love interest is a farmer, though, which is no more exalted socially) and there's a kind of fated mate trope by way of an ability to engage in remote communication, but it's one both parties have accepted.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Lawless, for the rec. Just ordered a copy from the library...

Delete