CONTEMPORARY

Emma Barry, Party Lines

A cynical white Democratic operative finds himself drawn to the

Economist-reading Latina he meets on a plane—and who turns out not to be as politically liberal as he assumed. In fact, she turns out to be his Republican opposite, campaign manager to the Republican candidate for President. Filled wth fascinating details about life on the presidential campaign trail, the frustrations of both racial stereotypes and racial tokenism, and the precarious position one is put in not knowing whether the lack of appreciation one feels is due to sexism, racism, personality conflicts, or a combination of all of the above,

Party Lines makes for a fittingly feminist conclusion to Barry's outstanding DC insider trilogy,

The Easy Part.

Sonya Clark, Good Time Bad Boy

A quiet but immensely appealing December-May romance featuring a down-on-his-luck country music star and a pulling-herself-up-by-her-bootstraps waitress who meet when the singer returns to his hometown after one too many drunken onstage turns. Especially appealing here is that Clark doesn't play the "bad boy who is really good underneath it all" card; our hero, 41-year-old Wade, is pretty much a jerk at novel's start, not anyone whom a woman with any sense of self-respect would want to get involved with. Yet as Wade gradually starts to get his own act together, remembering that he he used to be something more than the Good Time Bad Boy heroine Daisy believes him to be, and starts writing songs about past and present, image and reality, he becomes far more appealing as a romantic interest for smart, determined Daisy.

Victoria Dahl, Taking the Heat

It would hardly feel like a best of RNFF list without a book by Victoria Dahl. This year's entry features a unconventional (at least for Dahl) heroine, one distinctly lacking in self-confidence, in spite of her new job as a tell-it-like-it-is sex columnist. How can you not love a novel with a heroine who declares at an open mike night: "There is nothing flattering about someone wanting to bone you.... I hear some disagreement, but let me be clear. There are men out there who will put their penises in a tree. There are men out there who will put their penises in sheep. You do not need to feel flattered that a man wants to put his penis inside you." And with a too-nice-to-be-true bearded librarian hero? Especially one that interrogates the problematic aspects of male niceness?

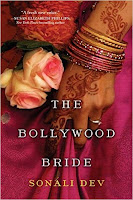

Sonali Dev, The Bollywood Bride

In rich, lyrical prose, Dev tells the story of a Bollywood star who, as a young girl, broke with her first love out of fear of the illness she might one day inherit via her unstable mother, and who now find herself once again in his orbit years later during the marriage festivities of their mutual friend. Rather than glorify female self-sacrifice, as so many romances do, Dev's tale insists that self-sacrifice is in many ways the coward's way out, a running away not only from one's problems, but from one's true self.

Rebecca Rogers Maher, Rolling in the Deep

A novel that opens, rather than ends, with a fairy tale ending: single mom Holly Ward and fellow big box chain store worker Ray Lopez go in together on a ticket and strike it rich in the Powerball lottery. Maher's story isn't interested in allowing readers to vicariously live out their dreams of untold riches by watching empty placeholder characters spend and spree on their behalves. But nor is it a cautionary tale, warning readers not to wish for the sun for they'll only get burned. Instead, it is a thoughtful attempt to understand what it means to be happy, and to what extent wealth, and romance, can contribute to the pursuit of same.

Cara McKenna, Give It All

On the outside, lawyer and PR manager Dunch Welch appears to be cool, controlled, and utterly contemptuous of anyone who lacks his looks, class, and intelligence. But when he's accuse of taking bribes during a casino development project, Duncan's highly-polished surface develops a few telling cracks. Cracks that never-get-attached bar owner Raina Harper is all too interested in breaking wide open. Especially love Raina's gender-bending admission that "I don't feel like being taken care of by anybody... I'd must racher be needed than do the needing." Care to guess who ends up rescuing who at the novel's climax?

Mary Ann Rivers, My Only Sunshine

An unusual alternating dual pov novella, with one strand written from the third person past tense point of view of Mallory, purportedly from the memoir adult Mallory wrote about her crush on John, now a famous musician, and the other from John's first person present tense point of view, describing their reunion as adults. Such a reunion could have felt schmaltzy, or unconvincing, in the hands of a less talented writer. But Rivers, who makes the unconventional choice to have the hero, rather than her "Venus-covered-in-sea-foam-"bodied heroine, be the one still learning to cope with adult life, has the writing chops to make a more-than-persuasive case for the power of adolescent love, and its potential to last far into adulthood.

Sherry Thomas, The One in My Heart

Thomas proves herself as adept at penning contemporary romance as she is at crafting historical in her contemporary debut in this subtle first-person portrait of a New Yorker whose one-night stand with a compelling stranger turns into something far more complicated than she could ever have expected. Emotionally-distant heroes are a dime a dozen in romance; creating a convincing, yet still appealing heroine who is closed off from her feelings is a far more uncommon achievement.

YA/NA

Sarina Bowen, The Shameless Hour

You might not think that a romance that explores the connections between frankness about sexually-transmitted diseases, slut-shaming, and the policing of young women's sexuality would be anything more than a preachy, plodding tract. Yet such is Bowen's skill that social critique merges seamlessly with compelling romance in this story of sexually free Bella, student-manager of Harkness College's male hockey team, and her romance with a younger student who is in many ways her exact opposite: Dominican to her white; working class to her ownership class; family-loving to her family-rejecting; and above all, serious to her casual, especially when it comes to sex. A trenchant dissection of the way that privileged men often use shame to control female sexuality, and the corroding effects of such sexual shame on young woman, as well as a touching romance about how to reach a place of both shamelessness and caring when embracing your own sexual desires.

A J Cousins, The Girl Next Door

The immensely entertaining sidekicks in Cousins'

Off Campus get their own story in

The Girl Next Door, which moves from the first book's college setting to a first job in the big city milieu. When Cash Carmichael's cousin, Denny, flees to Cash after his announcement that he was gay goes over like a lead balloon with his privileged family, Cash knows he needs to bring in big-time help. One-time college fuck-buddy, iconoclastic, feminist, bisexual Steph provides it, and more, and soon Cash is realizing how badly he fucked up by not taking her, not taking them, more seriously back in college. Especially when Steph insists on keeping Cash in the fuck-buddy zone. You might think reading an entire novel from the point of view of a privileged, not entire quick-on-the-draw heterosexual "bro" might not be all that comfortable, but Cousins does amazing work conveying the character and voice of a young man who should embody everything conventional and oblivious, but who is open and kind enough to learn that there are other, equally valid ways of being in the world, and to embrace the unconventional in his friends, his family, and even, occasionally, himself.

Emery Lord, The Start of Me and You

On the cusp of her junior year of high school, Paige Hancock is hoping to break free of her identity as the "Girl Whose Boyfriend Drowned." But Lord's story is not just an exploration of teen romantic grief; it also touches upon what-ifs that can never be realized; gift for time lost to illness; for friendships that change and die; for parents who aren't a part of your life; for grandparents who lose the vitality they once had. Lord never suggests that falling in love is a cure-all for any of these griefs. But her novel does set forth the hope that good friends, as well as caring romantic partners, can provide an extra paddle as one navigates its turbulent waters.

Courtney Milan, Trade Me

The titular "trade" results from immigrant Tina Chen losing her cool when, during a discussion of food stamps in class, fellow college classmate (and billionaire tech genius) Blake Reynolds makes a thoughtless comment, one that demonstrates how little he knows what it is like to live outside the bounds of middle class comfort. "Try trading lives with me. You couldn't manage it, not for two weeks," Tina challenges. To her utter shock, Blake takes her up on it. What makes the story intriguing is that Blake's acceptance stems not from a manly desire to prove himself, but from his desire to run away from his own fears, fears that are gradually revealed over the course of the novel. Thumbs up to Milan for presenting each protagonist's parent, a parent who in another author's hands would have clearly been labeled "villain," as rounded, intelligible, and above all sympathetic, complementing the book's larger themes of looking beyond the surfaces and understanding and confronting one's own fears.

Penny Reid, Elements of Chemistry

Hot billionaires falling obsessively in love with sweet, innocent college girls are not RNFF's usual cup of tea. Nor are NA angst-fests. But when the heroine of the billionaire romance is an awkward, self-effacing, but dead-honest dork, and the angst is the result not of outside evil elements, but of genuine misunderstandings between our protagonists, well, then, that's entirely different type of tea altogether. That Reid writes with quirky humor only adds to the pleasure of this sendup/embrace of contemporary romance stereotypes. "I'm not willing to settle for being with someone who

sometimes treats me well. I'd rather be alone."

HISTORICAL

Deanna Raybourne, A Curious Beginning

An auspicious beginning to Raybourn's latest Victorian mystery series, with a heroine who definitely puts the "un" in "unconventional." Young lepidopterist Veronica Speedwell returns from overseas travels to England to bury her last relative, only to discover that her ancestry may be a bit more complicated than she originally thought. And that several dangerous men seem to want to kill her because of it. Whether fleeing with a mysterious German baron, on the run with a traveling circus, or cataloging the holdings of an aristocratic natural historian, Veronica's rational yet intuitive first-person narration provides amusing commentary on her suddenly eventful life, as well as her budding relationship with a fellow naturalist who is as impulsive and emotional as Veronica is strategic and logical.

K J Charles, A Seditious Affair

Most reviewers would likely place Charles' novel in the "erotic romance" category. Yet her skill in making history central to her characters' identities, as well as their romantic conflict, puts her book clearly in the genre of the "historical" for me. Silas Mason and Dominic Frey would seem to have nothing in common—except for their sexual proclivities. Yet as the trysts between two men, one a radical bookseller and rabble-rousing pamphleteer, the other a conservative government official, continue over the course of months, and their sexual play leads to actual sharing of thoughts and ideas, they find to their shock that their differences spark a closeness neither of them could ever have imagined. If only Dom were not in charge of ferreting out sedition. And Silas were not still halfheartedly supporting his radical friends, even while he grows more and more disenchanted by their ridiculous hopes that they might have actually have a chance to overthrow the government....

Alyssa Cole, "Let it Shine" in The Brightest Day anthology

Cross-race romance has become common in contemporary romances, but its far more rare in historicals. Cole's 1950's set-novella showcases the courage it takes to engage in the struggle for African American civil rights, both for a daughter raised to be a "respectable" black woman and for a son raised to be a scholarly, obedient Jewish boy. Especially when their commitment to social justice becomes entangled with their growing feelings for one another.

Alyssa Everett, The Marriage Act

Wed in haste, repent at leisure. That's been the theme of John Welford's life for the past five years, after marrying the gorgeous daughter of his mentor, only to discover in the most embarrassing way that she preferred another. Leaving Caroline in England while he pursued his diplomatic career, John had little idea that his wife had never told her father of the estrangement, and is more than a little shocked when, upon his arrival home, she insists that he travel with her to visit said father, who is desperately ill. As the two travel together, we see that their estrangement is not due to a simple misunderstanding, but to real differences in personality and beliefs. Yet those very differences may just be why they are actually quite suited to one another, something they gradually begin to understand as they come to know one another as individuals, rather than as terrifying older husband and scheming immature wife.

Rose Lerner, True Pretenses

A Jewish con man thinks to swindle a nice English wife for his younger brother but ends up wanting her for himself. A fascinating exploration of cultural identity and cultural stereotypes, and the ways in which both influence our relationships with family and with lovers. Not to mention the appealing slow-build romance between two people who have always had to wear masks as they confront the world.

EROTIC ROMANCE

Molly O'Keefe, Everything I Left Unsaid

Instead of dancing blinding on the line between domineering hero and abusive hero, as so many other popular hetero erotic romances do,

Everything I Left Unsaid puts the issue of abuse front and center, even while giving readers crazy-hot sex scenes, too. Where do you draw the lines between appealing and abusive? Is niceness always a positive trait, or one that only leaves a woman open to exploitation and harm? Can a man be simultaneously controlling and kind? How little control does a victim have over her own life, and how much of her own behavior is self-deception, an act of complicity with her own abuse? Just a few of the unexpected questions O'Keefe's unusual erotic romance asks readers to consider.

Lilah Pace, Asking For It

One of the most talked-about romances of the year, and deservedly so, for its blunt explorations of intersections between rape culture and rape fantasy. One part of Vivienne, a white privileged New Orleans girl who moved to Texas to earn a Ph.D. in art, is sickened by her obsession with her own fantasies of being raped. Especially since she was raped in fact as a teen. But another takes deep pleasure in indulging those fantasies. When she discovers a man as equally invested in role-playing rape fantasies as she is, is her participation the height of psychological illness? Or a healthy way to work on her own sexual fixations? No easy answers, but Pace's willingness to ask the questions is a truly feminist move.

LGBTQ

Alex Beecroft, Blue-Eyed Stranger

Beecroft tackles big issues—how to cope with depression; the way history is taught to schoolchildren; which aspects of one's identity to hide and which to reveal—in this m/m romance set in the context of British historical reenactment groups. The son of African immigrants, schoolteacher Martin Deng insists on showing his kids that the was was not an all-white affair. But being in the closet about his sexuality creates major problems in his growing romance with Billy Wright, a white man dealing with mental health challenges. Social justice themes are not simply tacked on here, but are integral parts of both of Beecroft's complex characters.

Heidi Cullinan, Love Lessons series

One of my real pleasures this reading year was discovering the work of Heidi Cullinan. Unlike many m/m romance writers, Cullinan does not simply write two romance heroes who could both easily pass as straight; her male protagonists span the spectrum from buff athletes to effeminate twinks. And her stories insist that all have the right to the identity "masculine." Her 3 (and counting)

Love Lessons books (

Love Lessons, Fever Pitch, and

Lonely Hearts), all centered on the members of a midwestern Lutheran college singing group, also insist on the importance of gay men "paying it forward," helping those who come after them find their footing in a supportive, welcoming LGBTQ community.

Alexis Hall, For Real

Cynical, world-weary older trauma doctor Laurie, who prefers the submissive role in the bedroom, finds his surprising match in inexperienced but persistent Toby Finch, who gradually wears down Laurie's doubts about taking advantage of his far younger dom. Hall's overt political agenda—to write a romance that doesn't deny that "dominance and submission can exist within a dynamic between two perfectly ordinary people, simply because that's what they're in to"—never interferes with his crafting of intriguing, complex, and likable characters, characters whose sexual preferences seem strikingly at odds with their everyday identities. Not just one of the best kinky romances of the year, but one of the best romances of the year, full stop.

* Added 3/18:

Author Santino Hassell has been accused of widespread abusive behavior (see "The Santino Hassell debacle" for specific details). Readers may wish to consider these accusations before deciding whether or not to read Hassell's books. (JCH)

Santino Hassell, Sutphin Boulevard

Another welcome discovery for me (thanks, Queer Romance Month!) was the work of Santino Hassell, who brings a welcome working class perspective to a genre that is all too often filled with unattainable fantasies of ownership-class privilege. In the first of his

Five Boroughs series, Hassell presents two longtime friends, Michael Rodriguez and Nunzio Medici, who have helped each other navigate the challenges of dysfunctional families, the red tape of teaching in NYC's public schools, and the gay city scene for more than two decades. An unexpected threesome gives Michael a taste of Nunzio as lover, as well as a hint of Nunzio's true feelings for his longtime friend. But as Michael's family and work lives begin to implode, can Michael risk losing Nunzio's friendship in the hopes for that elusive something more?

P. D. Singer, A New Man

Offering both the emotional pleasures of romance and the intellectual pleasures of social and medical science, Singer's m/m romance asks readers to consider what it means to identify as straight or gay, masculine or effeminate, asexual or sexually desiring, and how biology may influence each of these identities. Particularly when one's physical body undergoes unexpected changes, as does college student Chad after a medical crisis leaves him in need of hormone therapy.

Nell Stark, The Princess and the Prix

A romance about an aggressive, hard-partying, womanizing race car driver with a troubled backstory who reforms after falling for a shy, brainy philanthropist/princess? And it's feminist? Yes, when that race car driver happens to be a woman. Stark's Grand Prix romance asks both us and its protagonist to think about just what gender equality might mean for a woman working in a primarily male realm, all within an appealing opposites-attract love story. A fairy-tale romance with a surprisingly feminist punch.

FANTASY

Ilona Andrews Magic Shifts

I wasn't very fond of the previous two books in Andrews' long-running Kate Daniels series, but this latest installment gets the series back on gender-equal grounds. After a devil's bargain with her evil father leaves Kate and the Beast Lord exiled from Curran's pack of shapeshifters, the two begin to carve out an life for themselves and their foster daughter, Julie, in a post-magic shifted Atlanta. But when a pack member goes missing, and the new Beast Lord refuses to get involved due to intra-pack politics, Kate and Curran once again find themselves in the midst of another battle for the city—and this one not driven by Kate's father. Or is it? "I will kill anything that tries to hurt you," he said, his voice quiet. "I know. I will kill anything that tries to hurt you," I told him. Perhaps not the most romantic of declarations, but one eminently suitable for this true kick-ass couple.

Bec McMaster, Of Silk and Steam

"What could any man ever give me? I'm the head of my House, a woman on the Council. What man wouldn't try to take that from me?"

"Not all men are created equally. Maybe you should find one who isn't threatened by your achievements. Someone who finds such accomplishments to be part of the fascination."

The 5th installment of McMaster's London Steampunk series finally allows us inside the head of charming Leo Barrons, brother to the heroines of the first two books, as he becomes entangled with powerful Aramina (Mina) Duvall, the only female vampire in the London aristocracy. Entwining discourses of gender equality, such as the one quoted above, with those of mutual submission to the beloved ("He owned her. The most terrifying thing in the world once. But he could only own her if she allowed it, and she held that power in her hands"), McMaster insists that the two are not opposed, but mutually supportive. Not sure I always buy the message, but its far more appealing that the plethora of paranormal romances that ignore the opposition altogether, crafting purportedly kick-ass heroines who never seem to realize how much power they're ceding to their male lovers.

What books would you nominate as the best romances of 2015 for feminist-inclined readers?