Yesterday, Romance Writers of America® announced the list of finalists for its RITA Awards, which the organization bestows in recognition of excellence in publishing romance writing. So it's also time for the annual RNFF blog post with data on the state of racial diversity amongst the RITA finalists, with added info on the race/ethnicity and sexuality of the characters of the finalist books.

For the second year in a row, all RITA contest entrants were required to submit a pdf copy, rather than print copies, of their books. Entrants could also submit either an epub or a kindle mobi file as well, for the convenience of judges. As this was not a change that changed the basic demographics of the entrants pool, as the switch from all print to pdf was in 2017, it's not surprising that a similar number of self-published books were chosen as finalists this year as last (22, by my count).

Representation of queer characters is a bit down from last year, although there is one lesbian romance, as compared to no lesbian romances last year.

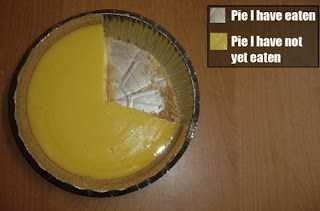

What about representation of race/ethnicity? What do those numbers look like?

Not good. Not good at all.

Many books, and many author bios, don't explicitly state protagonists' or authors' race. So the calculations below are based on the following:

• In cases where I'd read the book, I knew the race of the protagonists, either by being directly told in the narrative, or from context clues in the book

• In cases where I had not read the book, I examined book covers, book descriptions, Goodreads book reviews, and character names for hints about protagonists' racial and ethnic backgrounds, and made my best guess. Major room for error here, so if you see any mistakes below, please let me know!

• Similarly, for authors with whom I was familiar, and/or who had discussed their own racial backgrounds in public, I went with self-represented racial identities. I had to rely on author photographs and my best guesses for the rest. Two finalists do not include author photos on their web sites, so I classified them as white. Again, room for error (and correction) here.

2018: 74

2017: 78

2016: 85

# of authors of color:

2018: 3***

2017: 5-6

2016: 4-6

% of authors of color:

2018: 4%***

2017: 6-7.7%

2016: 4-7%

Overall # of protagonists: 149 (73 * 2, 1 * 3 [one erotic romance features a ménage-a-trois])

# of protagonists of color

2018: 8

2017: 13

2016: 5

% of protagonists of color

2018: 5.3%

2017: 8.3%

2018: 2.9%

of queer protagonists:

2018: 10 (8 in m/m romances, 2 in a lesbian romance)

2017: 12

2016: 8

% of queer protagonists:

2018: 6.7%

2017: 7.6%

2016: 4%

Individual Sub-Genre Numbers:

Contemporary Romance Long

# of finalists: 7

# of authors of color: 0

# of protagonists of color: 2

# of queer protagonists: 0

Contemporary Romance: Mid-Length

# of finalists: 11

# of authors of color: 0

# of protagonists of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 4

Contemporary Romance: Short

# of finalists: 8

# of authors of color: 0

# of protagonists of color: 0*

# of queer protagonists: 2

Erotic Romance:

# of finalists: 4

# of authors of color: 0

# of protagonists of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Historical Romance: Long

# of finalists: 4

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Historical Romance: Short

# of finalists: 6

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Mainstream Fiction with a Central Romance

# of finalists: 5

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 1

# of queer protagonists: 0

Paranormal Romance

# of finalists: 7

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Romance Novella

# of finalists: 7

# of authors of color: 1

# of characters of color: 1

# of queer protagonists: 2

Romance with Religious or Spiritual Elements

# of finalists: 4

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Romantic Suspense

# of finalists: 7

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 1

# of queer protagonists: 0

Young Adult Romance

# of finalists: 4

# of authors of color: 1

# of characters of color: 4**

# of queer protagonists: 0

It's more than depressing that the representation of authors of color in the RITA finalist pool has decreased, despite recent efforts by the organization to better support its members of color. What else can RWA do to begin to address what is a glaringly obvious problem of bias in its judging system?

More than a year ago, RWA stated that it was in the process of polling its membership about demographic issues, but to date I don't believe that information has been made public. Does RWA have any sense of how the demographics of RWA membership compares to the demographics of the U. S. as a whole? And how its overall demographics compare to the demographics of the finalists and the judges? Compiling and sharing such information with its membership would be a good place to start.

Another intervention would be to begin asking entrants for demographic information about themselves and about the characters in the books they are submitting. Percentages could then be compared to the percentages in the finalist pool.

Or RWA could consider revamping the way the entire contest is judged, and create a process in which systemic racism could be, if not entirely eliminated, at least majorly curtailed. I'd strongly urge the Board to create a committee or working group to study the issue in the coming year.

I know more than a few authors who would be interested in serving...

US Census data on race/ethnicity (2016)

White: 61.3%

POC: 40.9%

2018 RITA Finalists by race/ethnicity

White: 97.3%

POC: 4%

* Caitlin Crews' A Baby to Bind His Bride includes this description of its hero: "amalgam of everything that was beautiful in him. His Greek mother. His Spanish father. His Brazilian grandparents on one side, his French and Persian grandparents on the other." I'm not counting this hero as a POC.

** one of these books, written by a white author, features Latinx characters, one of whom is a gang member. I have counted these characters as POC, despite some concern that this representation may be problematic. I have not yet read the book in question.

*** My original post listed 2 authors of color, not 3. I've updated the numbers accordingly, given the comments below.

For the second year in a row, all RITA contest entrants were required to submit a pdf copy, rather than print copies, of their books. Entrants could also submit either an epub or a kindle mobi file as well, for the convenience of judges. As this was not a change that changed the basic demographics of the entrants pool, as the switch from all print to pdf was in 2017, it's not surprising that a similar number of self-published books were chosen as finalists this year as last (22, by my count).

Representation of queer characters is a bit down from last year, although there is one lesbian romance, as compared to no lesbian romances last year.

What about representation of race/ethnicity? What do those numbers look like?

Not good. Not good at all.

Many books, and many author bios, don't explicitly state protagonists' or authors' race. So the calculations below are based on the following:

• In cases where I'd read the book, I knew the race of the protagonists, either by being directly told in the narrative, or from context clues in the book

• In cases where I had not read the book, I examined book covers, book descriptions, Goodreads book reviews, and character names for hints about protagonists' racial and ethnic backgrounds, and made my best guess. Major room for error here, so if you see any mistakes below, please let me know!

• Similarly, for authors with whom I was familiar, and/or who had discussed their own racial backgrounds in public, I went with self-represented racial identities. I had to rely on author photographs and my best guesses for the rest. Two finalists do not include author photos on their web sites, so I classified them as white. Again, room for error (and correction) here.

Overall Statistics:

# of finalists:2018: 74

2017: 78

2016: 85

# of authors of color:

2018: 3***

2017: 5-6

2016: 4-6

% of authors of color:

2018: 4%***

2017: 6-7.7%

2016: 4-7%

Overall # of protagonists: 149 (73 * 2, 1 * 3 [one erotic romance features a ménage-a-trois])

# of protagonists of color

2018: 8

2017: 13

2016: 5

% of protagonists of color

2018: 5.3%

2017: 8.3%

2018: 2.9%

of queer protagonists:

2018: 10 (8 in m/m romances, 2 in a lesbian romance)

2017: 12

2016: 8

% of queer protagonists:

2018: 6.7%

2017: 7.6%

2016: 4%

Individual Sub-Genre Numbers:

Contemporary Romance Long

# of finalists: 7

# of authors of color: 0

# of protagonists of color: 2

# of queer protagonists: 0

Contemporary Romance: Mid-Length

# of finalists: 11

# of authors of color: 0

# of protagonists of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 4

Contemporary Romance: Short

# of finalists: 8

# of authors of color: 0

# of protagonists of color: 0*

# of queer protagonists: 2

Erotic Romance:

# of finalists: 4

# of authors of color: 0

# of protagonists of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Historical Romance: Long

# of finalists: 4

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Historical Romance: Short

# of finalists: 6

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Mainstream Fiction with a Central Romance

# of finalists: 5

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 1

# of queer protagonists: 0

Paranormal Romance

# of finalists: 7

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Romance Novella

# of finalists: 7

# of authors of color: 1

# of characters of color: 1

# of queer protagonists: 2

Romance with Religious or Spiritual Elements

# of finalists: 4

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 0

# of queer protagonists: 0

Romantic Suspense

# of finalists: 7

# of authors of color: 0

# of characters of color: 1

# of queer protagonists: 0

Young Adult Romance

# of finalists: 4

# of authors of color: 1

# of characters of color: 4**

# of queer protagonists: 0

It's more than depressing that the representation of authors of color in the RITA finalist pool has decreased, despite recent efforts by the organization to better support its members of color. What else can RWA do to begin to address what is a glaringly obvious problem of bias in its judging system?

More than a year ago, RWA stated that it was in the process of polling its membership about demographic issues, but to date I don't believe that information has been made public. Does RWA have any sense of how the demographics of RWA membership compares to the demographics of the U. S. as a whole? And how its overall demographics compare to the demographics of the finalists and the judges? Compiling and sharing such information with its membership would be a good place to start.

Another intervention would be to begin asking entrants for demographic information about themselves and about the characters in the books they are submitting. Percentages could then be compared to the percentages in the finalist pool.

Or RWA could consider revamping the way the entire contest is judged, and create a process in which systemic racism could be, if not entirely eliminated, at least majorly curtailed. I'd strongly urge the Board to create a committee or working group to study the issue in the coming year.

I know more than a few authors who would be interested in serving...

US Census data on race/ethnicity (2016)

White: 61.3%

POC: 40.9%

2018 RITA Finalists by race/ethnicity

White: 97.3%

POC: 4%

* Caitlin Crews' A Baby to Bind His Bride includes this description of its hero: "amalgam of everything that was beautiful in him. His Greek mother. His Spanish father. His Brazilian grandparents on one side, his French and Persian grandparents on the other." I'm not counting this hero as a POC.

** one of these books, written by a white author, features Latinx characters, one of whom is a gang member. I have counted these characters as POC, despite some concern that this representation may be problematic. I have not yet read the book in question.

*** My original post listed 2 authors of color, not 3. I've updated the numbers accordingly, given the comments below.