When my family moved from Connecticut to Vermont when I was in the 10th grade, I had to transition not just from living in suburbia. No, it also meant a transition from a large public school with tracked classes to a small private school with only two tracks: Catholic and non-Catholic. Since you had to pay $100 extra if you signed up as a non-Catholic, my thrifty parents checked the "Catholic" box, even though my religious upbringing had hardly been traditional. A bit of Methodism, a bit of Catholicism, a bit of 70's spiritualism, and a whole lot of "screw it all," especially after the doctrinaire nun who taught my 3rd grade CCD class told me that my guinea pig, who had just died, was certainly not going to heaven (only people, not animals, have spirits and a chance at the afterlife). But at Mount St. Joseph Academy, it was a "yes or no" question, with no handy box for filling in further information available.

Checking that "Catholic" box, though, meant more than just a reduction in tuition. It also meant that I had to take Religion class. Most of my schoolmates, having attended Catholic school since kindergarten, tended to either nod in agreement or nod off in boredom while the nun or priest or occasionally the lay person heading Religion class taught his or her lesson. But I often found myself challenging the teacher, pushing at things that my classmates took for granted, or had long ago learned it wasn't worth the questioning. Asking the "why" questions that often excited, and often annoyed, the person at the front of the room led other students to look at me as if I were crazy for bothering, but I took pride in being a questioner, of not accepting the easy answer.

I've often wondered what I would have been like if, like my Catholic school classmates, I had been brought up differently? If I had been taught from my earliest days that the tenets of Catholicism, and only Catholicism, were of course the right way to live my life and to judge the moral choices of myself and of others? Would I still have questioned those premises? What leads someone to question something that everyone around them takes for granted?

For sixteen-year-old Jonathan Cooper, it's not being thrust into an unfamiliar setting. In fact, he's been attending Spirit Lake Bible Camp for seven years now, drawn by its strong Protestant ethos and the caring of its leaders and counselors. They know how hard it is having a father in the military, away for years at a time, how hard it is being the man of the house. They listen, rather than just preach. And they know asking WWJD? (What would Jesus Do?) is a way to get him thinking about his moral and ethical choice, rather than just shoving them down his throat. Jonathan feels so at peace at Spirit Lake that he's even imagined himself becoming a junior counselor next year.

No, it's not the unfamiliar setting, but Jonathan's own unfamiliar feelings, that set him to questioning. When a new boy with bright red hair and a rainbow-colored wristband challenges the camp blowhard for saying "That's so gay!" to Jonathan's plans to go out for acting rather than for the more obviously masculine Outdoor Rec program, and Jonathan finds himself not just breaking up the fight, but befriending the newcomer. And then finding himself attracted to Ian McGuire. Not just as a friend, but emotionally, and physically, attracted. How can a pious, God-loving boy be experiencing such things?

None of the adults at Spirit Lake condone overt gay-bashing. They preach the gospel of love, not hate. As Jonathan's cabin counselor tells his campers during a discussion of temptation:

That's why we need to love people who are in bondage to sin and especially to this lifestyle. We are not to bully then or h ate them. Rather, we are to shine God's love into their lives and pray for them. You've heard the phrase Hate the sin and love the sinner, right? That goes double for homosexuals.

But most are equally certain that homosexuality is wrong, a sin, an abomination. When the camp leader, Paul, begins to suspect Jonathan and Ian's feelings for one another, he tells him he fears Jonathan is "under some kind of satanic attack right now, and you are being tempted by the flesh to deviate from your true identity in Christ" (Loc 1768).

Not all the adults think this way, though. Two of the camp's adults—significantly, both outsiders in different ways—offer Jonathan other ways of thinking about his identity, about his attractions and his feelings. And about what his religion has to say about same-sex desire.

Is it possible for an Evangelical Christian to also be gay? In literature and in popular culture, Evangelical Christianity is often painted as monolithic, black and white, intolerant of difference. Juliann Rich, a woman who grew up in an Evangelical household, both acknowledges and refutes this characterization, offering hope through her characterization of Jonathan, Ian, and Jonathan's more unconventional Christian adult mentors to devout young men who find themselves not fitting the heterosexual mold yet not wanting to sacrifice their religion for the sake of their sexuality.

Photo credits:

Rainbow wristband: Rainbow Depot

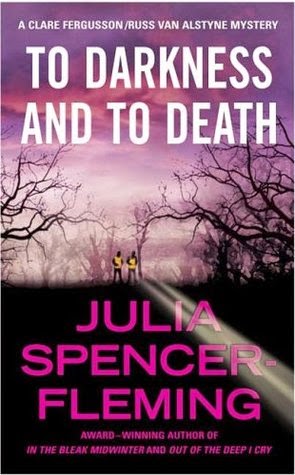

Bold Strokes Books, 2014