I am, by nature, a fixer. Whenever I hear someone talk about a problem, I immediately start to think about all the possible ways I could act to make that problem go away. It can be a really annoying habit, this urge to want to fix everything, especially when it comes to people. Not everyone needs, or even wants, to be fixed. Even if the larger society around them thinks they should do something to make their situation better, a lot of people are perfectly happy being the way they are. Because broken isn't always fixable, especially when it comes to people. And also because one person's "broken" may just be another person's "different."

Reading Tamsen Parker's latest contemporary romance, The Inside Track, gave me a much-needed reminder of this. And did so while making me laugh harder than I can ever remember laughing while reading a romance.

The Inside Track's two white protagonists, financial advisor Dempsey Lawrence and boy band guitarist Nick Fischer, do not function in socially conventionally ways. Readers of Parker's earlier books featuring License to Game (Love on the Tracks and Thrown Off Track), the boy band on the cusp of aging out of their audience, will remember Nick as the goofball screwup of the group, an eight-year-old boy in a 28-year-old's body. Nick's more than just a bundle of impulsivity; he fidgets, he wrestles, he talks a mile a minute about the most fascinating, and often disgusting, things. He's never worried about making a fool of himself; he adores being the center of attention. Witness the book's opening scene, in which we find a drunken Nick with the accordion which once belonged to Lawrence Welk, an accordion which he's "borrowed" from the wall of the Los Angeles restaurant where he was dining. He's playing it outside, in the middle of a fountain—stark naked. If only he had his unicycle, too...

Using close first person, Parker gives readers access to the whirling pinball inside Nick's head, following his thoughts as they carom from topic to topic, making leaps of association that are as amazingly imaginative as they are hilarious:

Maybe these police officers would like to be my friends. Because if any of my guys were here, they probably would've suggested that climbing into a fountain, naked, with an accordion was maybe not my best idea. Or at least they would've held my goddamn pants so some dickwad wouldn't take them. Fucking pants thieves. That's just low. (Kobo epub, Chapter 1, page 7)

Or this, from the second chapter, where Nick is serving out his community service sentence for the aforementioned accordion incident by speaking with kids at a local performing arts school about managing your money when you're a creative. Nick on the coolness of spreadsheets:

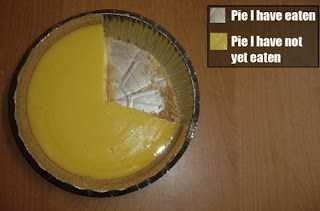

"They're like wizards, guys. Seriously. Magic on your screen. They do math for you, but in a cooler way than a calculator. And then you can even make pie charts. Pie charts are really fu— falutin' rad. I don't know about you guys, but like, sometimes numbers make my head hurt? But I'm totally game for colors and shapes. And pie. Pie is delicious. My favorite is probably key lime. Why do you think they call them pie charts instead of pizza charts? Because pizza is great, and it would make them sound way cooler. But then I guess they call pizzas pies, don't they? Which is weird. Because it's not like a real pie. Except in Chicago. You guys like deep dish?" (Ch. 2, p. 13-14)

Even after encountering Nick not under the influence, a reader who knows anyone with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is likely to be thinking "It's ADHD! Get diagnosed! Get some help!" But Parker is not interested in telling the story of a person whose life gets put back on track after receiving a welcome medical diagnosis. Sometimes, a diagnosis doesn't lead to an easy fix. As Nick reveals later on in the story, he was diagnosed as a child, but rebounding off the drugs proscribed to deal with the ADHD made him sullen and violent, and the meds themselves gave him a tic. So his family decided against medicating Nick's condition. Neurotypical is certainly not the word to describe Nick. But he and his family and bandmates have come to love him for who he is, not for who he should or could be if only the drugs had worked better for him.

Parker pairs attention-hound Nick with perhaps the most unlikely of opposites: a woman who has not left her property for more than five years. Thirty-four year old Dempsey, a former teen tv star, experienced major trauma due to her career. She, unlike Nick, takes medication, because the trauma has left her with debilitating problems; her meds help curb her anxiety and panic attacks, and allow her to function as a financial planner to other young show business kids who don't mind working with someone over the phone. But neither her doctors nor "a shit ton of pharmaceuticals" have been able to rid Dempsey of her agoraphobia. A shiny new boyfriend certainly won't, either, as Dempsey makes clear to Nick when she first tells him about her condition:

"You're not going to be the hero here. There are no white horses or castle moats or needle-pricked fingers. You should assume that I'm never leaving this quarter-acre lot ever again and make your choices based on that. There's the door." (Ch 6, p 9)

But unconventional Nick doesn't think Dempsey's agoraphobia is as anathema to romance as she does: "I like you. I like being with you. And if I have to come here to hang out with you, then I will. I don't really feel like that's a big thing. No one's perfect." (Ch 6, p 10). Nick loves everyone's attention, but there's something about Dempsey's that is just off the charts compelling to him. Almost as if she can channel the cheering of a stadium full of people, just by herself. And Dempsey is equally charmed by Nick's intelligence, humor, and utter lack of guile. After being lied to over and over again in the past, Dempsey truly appreciates a man who isn't hiding anything.

As I read further on into their story, one part of my mind kept expecting some big plot event that would "fix" either Dempsey or Nick. Some danger to Nick would compel Dempsey to leave her house, and she'd find herself miraculously recovered. Or some new doctor would give Nick a different diagnosis, or would offer him a new drug that would calm down the impulsivity of his brain. And Parker throws out several plot complications that look like they might be headed in one of those directions—only to pull back and disrupt the common romance trope that falling in love will fix everything. Dempsey and Nick do help each other, not to fix themselves, but rather, to adapt to each other's needs, while keeping their own abilities and needs also in view. Those adaptations might be a bit on the unusual side for this particular couple, but its a process anyone, neurotypical or no, who is involved in a relationship must embrace if they are to make it past the first blush of romance.

Photo credits:

Lawrence Welk album: Treadwell's Music

Pie pie chart: EdwardTufte.com

Reading Tamsen Parker's latest contemporary romance, The Inside Track, gave me a much-needed reminder of this. And did so while making me laugh harder than I can ever remember laughing while reading a romance.

The Inside Track's two white protagonists, financial advisor Dempsey Lawrence and boy band guitarist Nick Fischer, do not function in socially conventionally ways. Readers of Parker's earlier books featuring License to Game (Love on the Tracks and Thrown Off Track), the boy band on the cusp of aging out of their audience, will remember Nick as the goofball screwup of the group, an eight-year-old boy in a 28-year-old's body. Nick's more than just a bundle of impulsivity; he fidgets, he wrestles, he talks a mile a minute about the most fascinating, and often disgusting, things. He's never worried about making a fool of himself; he adores being the center of attention. Witness the book's opening scene, in which we find a drunken Nick with the accordion which once belonged to Lawrence Welk, an accordion which he's "borrowed" from the wall of the Los Angeles restaurant where he was dining. He's playing it outside, in the middle of a fountain—stark naked. If only he had his unicycle, too...

Using close first person, Parker gives readers access to the whirling pinball inside Nick's head, following his thoughts as they carom from topic to topic, making leaps of association that are as amazingly imaginative as they are hilarious:

Maybe these police officers would like to be my friends. Because if any of my guys were here, they probably would've suggested that climbing into a fountain, naked, with an accordion was maybe not my best idea. Or at least they would've held my goddamn pants so some dickwad wouldn't take them. Fucking pants thieves. That's just low. (Kobo epub, Chapter 1, page 7)

Or this, from the second chapter, where Nick is serving out his community service sentence for the aforementioned accordion incident by speaking with kids at a local performing arts school about managing your money when you're a creative. Nick on the coolness of spreadsheets:

"They're like wizards, guys. Seriously. Magic on your screen. They do math for you, but in a cooler way than a calculator. And then you can even make pie charts. Pie charts are really fu— falutin' rad. I don't know about you guys, but like, sometimes numbers make my head hurt? But I'm totally game for colors and shapes. And pie. Pie is delicious. My favorite is probably key lime. Why do you think they call them pie charts instead of pizza charts? Because pizza is great, and it would make them sound way cooler. But then I guess they call pizzas pies, don't they? Which is weird. Because it's not like a real pie. Except in Chicago. You guys like deep dish?" (Ch. 2, p. 13-14)

Even after encountering Nick not under the influence, a reader who knows anyone with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is likely to be thinking "It's ADHD! Get diagnosed! Get some help!" But Parker is not interested in telling the story of a person whose life gets put back on track after receiving a welcome medical diagnosis. Sometimes, a diagnosis doesn't lead to an easy fix. As Nick reveals later on in the story, he was diagnosed as a child, but rebounding off the drugs proscribed to deal with the ADHD made him sullen and violent, and the meds themselves gave him a tic. So his family decided against medicating Nick's condition. Neurotypical is certainly not the word to describe Nick. But he and his family and bandmates have come to love him for who he is, not for who he should or could be if only the drugs had worked better for him.

Parker pairs attention-hound Nick with perhaps the most unlikely of opposites: a woman who has not left her property for more than five years. Thirty-four year old Dempsey, a former teen tv star, experienced major trauma due to her career. She, unlike Nick, takes medication, because the trauma has left her with debilitating problems; her meds help curb her anxiety and panic attacks, and allow her to function as a financial planner to other young show business kids who don't mind working with someone over the phone. But neither her doctors nor "a shit ton of pharmaceuticals" have been able to rid Dempsey of her agoraphobia. A shiny new boyfriend certainly won't, either, as Dempsey makes clear to Nick when she first tells him about her condition:

"You're not going to be the hero here. There are no white horses or castle moats or needle-pricked fingers. You should assume that I'm never leaving this quarter-acre lot ever again and make your choices based on that. There's the door." (Ch 6, p 9)

But unconventional Nick doesn't think Dempsey's agoraphobia is as anathema to romance as she does: "I like you. I like being with you. And if I have to come here to hang out with you, then I will. I don't really feel like that's a big thing. No one's perfect." (Ch 6, p 10). Nick loves everyone's attention, but there's something about Dempsey's that is just off the charts compelling to him. Almost as if she can channel the cheering of a stadium full of people, just by herself. And Dempsey is equally charmed by Nick's intelligence, humor, and utter lack of guile. After being lied to over and over again in the past, Dempsey truly appreciates a man who isn't hiding anything.

As I read further on into their story, one part of my mind kept expecting some big plot event that would "fix" either Dempsey or Nick. Some danger to Nick would compel Dempsey to leave her house, and she'd find herself miraculously recovered. Or some new doctor would give Nick a different diagnosis, or would offer him a new drug that would calm down the impulsivity of his brain. And Parker throws out several plot complications that look like they might be headed in one of those directions—only to pull back and disrupt the common romance trope that falling in love will fix everything. Dempsey and Nick do help each other, not to fix themselves, but rather, to adapt to each other's needs, while keeping their own abilities and needs also in view. Those adaptations might be a bit on the unusual side for this particular couple, but its a process anyone, neurotypical or no, who is involved in a relationship must embrace if they are to make it past the first blush of romance.

Photo credits:

Lawrence Welk album: Treadwell's Music

Pie pie chart: EdwardTufte.com

The Inside Track

License to Love #2

Indie published, 2019