For a genre that focuses so directly on emotions, romance has more than its fair share of emotionally distant, closed-off, and even repressed protagonists. The character arc for such protagonists typically involves moving from a stance that regards emotion as something to be feared and shunned to one that accepts and embraces emotional vulnerability. This past week, I read two contemporary romances, one after the other as it chanced, that featured such a character arc. One book's character was male, while the other was female. As feelings are so often coded as feminine, not masculine, I was curious to think and blog about how each of these stories—the third book in Christina Lauren's Beautiful series, Beautiful Secret, and the first contemporary romance by historical and fantasy author Sherry Thomas, The One in My Heart—presents the tasks and challenges that its emotionally distant protagonist must face and overcome.

The earlier books in Lauren's Beautiful series has been noted for its strong alpha male leads. Secret proves a departure, with gorgeous but "prim" and "stodgy" British urban planner Niall Stella cast in the role of hero (5). Though our heroine, unrestrained, ebullient American Ruby Miller prefers to think of him as "steady" and "restrained," there is no question that the stiff Mr. Stella is just about the last guy one would ever imagine engaging in a friendly bout of flirting. Even so, Ruby's been nursing a fierce crush on the thirty-year-old recently-divorced VP, a crush seems destined to remain unrequited.

Until Ruby and Niall are sent away to a month-long International Summit on Emergency Preparedness for urban infrastructure in New York City. Staying in the same hotel. On the same floor. Working together all day in the same tiny temporary office. Of course, Ruby's crush soon becomes glaringly obvious, even to the emotionally out-of-it Niall. And Niall finds himself more than a little intrigued. The uptight Brit isn't sure which is more shocking—the fact that a young, attractive, intelligent woman like Ruby finds dull old him of interest, or that his own long-dead passions are responding so immediately, and so intensely, to her.

Niall's personality isn't the only think holding him back, although growing up the quiet, introverted one amidst a large family of extroverts had definitely exerted its influence. Niall is also still trying to adjust to life after a sixteen-year relationship with the same woman, a relationship which he pretty much just went along with, and which he allowed to descend into boredom and even contempt with nary a protest. Not surprisingly, then, it is the female half of this relationship that does the majority of the heavy emotional lifting. Every time Ruby and Niall take a step forward, sexually, the inexperienced, logical Niall finds himself overthinking things, taking two steps back. The daughter of two psychologists, Ruby is used to talking about feelings, and isn't shy about sharing hers with Niall. But she also realizes that Niall's understanding of emotions is far different from hers, and that it will be her role to teach him more about how partners communicate. To Ruby (and to the reader), Niall seems more than worth it, if she can just crack open his layers and layers of protective shell. Patience will be the order of the day.

Until, that is, Niall proves particularly obtuse about Ruby's own emotions, acting in a way that any person with half an ounce of empathy should have realized would be not just hurtful, but deeply emotionally wounding. For me, the depiction of how Niall and Ruby recover from Niall's emotionally tone-deaf disaster proved the most interesting part of the book. For it drew a clear line in the sand about just how much a woman should have to carry the emotional weight of a relationship before said weight becomes too burdensome for her own self-respect. It's not groveling, nor his ham-handed attempt at a fairy-tale rescue (adding insult to injury), that brings Niall back into Ruby's life. Instead, it is a taste of his own medicine, time and emotional distance. Time for Ruby to lick her wounds and to recapture her sense of professional self-confidence, and to understand the importance of balance in a relationship:

But as soon as she'd said it, I knew that being back with Niall would be just as good. I wanted Niall just as much as I wanted to work with Maggie. And for the first time since [plot spoiler deleted], I didn't feel embarrassed for it, or that I was betraying some inner feminist thread by admitting how deep my feelings were. If I went back to Niall, some days he would be my entire life. Some days school would be. Some days they would occupy the same amount of space. And that knowledge—that I could find balance, that maybe I did need to separate my heart from my head after all—loosened a tension that had seemed to reside in my chest for weeks now." (360).

Lauren's novel is told in the first person, but with alternating points of view, allowing readers into Niall's head so that we can understand his emotions, even if Ruby (and Niall himself) don't. Sherry Thomas, in contrast, confines her story solely to the heroine's first person POV. It's only after you reach the book's ending that you realize just how significant that POV choice is; allowing us only into narrator Evangeline Canterbury shapes the story, and how readers respond to it, un expected ways.

Thomas's romance opens on a dark, rainy night, with Evangeline walking a deserted road. When a car comes abreast, both Evangeline and the reader can't help but be suspicious, even though the book's bright, sunny cover suggests that danger and suspense have no place in this romance. And this initial sense of suspicion carries over throughout much of the first half of the book. Is the man who offered Evangeline his car, and who then accepted her offer of a ride home, the man with whom Evangeline thought she was having a one-night (one-hour) stand but who later reemerges in her life, a man to be trusted? It's clear that wealthy, intelligent heart surgeon Bennett Somerset is deeply gifted at manipulation; he talks Evangeline into going out with him again, charms her into sleeping with him again, even convinces her that he needs her to pretend to be his fiancée so that he can reconnect with his long-estranged parents, who are part of Evangeline's family's New York city social circle. Is Bennett interested in Evangeline at all for her own sake? Or is he only using her to achieve his own ends?

I was so distracted by my worries over Bennett's intentions that it took me some time to pick upon the fact that Eva has her own emotional issues, too, even though Eva tells us early and directly that she is emotionally messed up: "My preferred method for dealing with everything that frightened, saddened, or unsettled me was to never speak of or even acknowledge it. In other words, I was incapable of emotional intimacy" (Kindle Loc 397). But because we're so tightly in Eva's head, and we don't seen inside the head of anyone else, someone who might give us some perspective about Eva, her own self-description doesn't resonate as much as it might have. In fact, it only became clear to me when Bennett began to shake off his own debilitating emotional crutch (in his case, pride) that Eva, too, has some emotional growing to do before she can make any kind of romantic relationship work. What initially looked like a sign of Bennett's emotional immaturity—his long-ago affair with a much older woman—eventually emerges as a sign of his skill at communicating, at connecting, with a romantic partner. Eva might be right to be initially suspicious of Bennett's intentions, but it is her own refusal to allow herself to be emotionally vulnerable that keeps those suspicions front and center throughout their relationship, and prevents her from allowing herself to engage emotionally to the same degree that Bennett has, and hopes to again. With her.

Interestingly, many Goodreads reviewers have responded far more negatively to the emotionally-distant Eva than they did to the emotionally-repressed Niall, even though her emotional issues are conveyed far less directly, far more subtly, than are his. A man in need of training in the ways of emotion and communication (by a woman) is acceptable, even welcome, given how gendered emotional work is in our society. But when a woman is the one who is emotionally closed-off, well, that character is far less comfortable for readers who take it for granted that it is the woman, rather than the man, who is the one responsible for maintaining a romantic relationship's emotional health.

What other emotionally repressed romance characters can you recall from your own reading? Are emotionally-repressed men more common (and/or more beloved) than emotionally distant women?

Photo credits:

Radio City: pixshark

Emotionally distant hearts: Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Tesla headlights: Tesla Motor Club

The earlier books in Lauren's Beautiful series has been noted for its strong alpha male leads. Secret proves a departure, with gorgeous but "prim" and "stodgy" British urban planner Niall Stella cast in the role of hero (5). Though our heroine, unrestrained, ebullient American Ruby Miller prefers to think of him as "steady" and "restrained," there is no question that the stiff Mr. Stella is just about the last guy one would ever imagine engaging in a friendly bout of flirting. Even so, Ruby's been nursing a fierce crush on the thirty-year-old recently-divorced VP, a crush seems destined to remain unrequited.

|

| Only one of the NYC spots in front of which Ruby takes a selfie... |

Niall's personality isn't the only think holding him back, although growing up the quiet, introverted one amidst a large family of extroverts had definitely exerted its influence. Niall is also still trying to adjust to life after a sixteen-year relationship with the same woman, a relationship which he pretty much just went along with, and which he allowed to descend into boredom and even contempt with nary a protest. Not surprisingly, then, it is the female half of this relationship that does the majority of the heavy emotional lifting. Every time Ruby and Niall take a step forward, sexually, the inexperienced, logical Niall finds himself overthinking things, taking two steps back. The daughter of two psychologists, Ruby is used to talking about feelings, and isn't shy about sharing hers with Niall. But she also realizes that Niall's understanding of emotions is far different from hers, and that it will be her role to teach him more about how partners communicate. To Ruby (and to the reader), Niall seems more than worth it, if she can just crack open his layers and layers of protective shell. Patience will be the order of the day.

Until, that is, Niall proves particularly obtuse about Ruby's own emotions, acting in a way that any person with half an ounce of empathy should have realized would be not just hurtful, but deeply emotionally wounding. For me, the depiction of how Niall and Ruby recover from Niall's emotionally tone-deaf disaster proved the most interesting part of the book. For it drew a clear line in the sand about just how much a woman should have to carry the emotional weight of a relationship before said weight becomes too burdensome for her own self-respect. It's not groveling, nor his ham-handed attempt at a fairy-tale rescue (adding insult to injury), that brings Niall back into Ruby's life. Instead, it is a taste of his own medicine, time and emotional distance. Time for Ruby to lick her wounds and to recapture her sense of professional self-confidence, and to understand the importance of balance in a relationship:

But as soon as she'd said it, I knew that being back with Niall would be just as good. I wanted Niall just as much as I wanted to work with Maggie. And for the first time since [plot spoiler deleted], I didn't feel embarrassed for it, or that I was betraying some inner feminist thread by admitting how deep my feelings were. If I went back to Niall, some days he would be my entire life. Some days school would be. Some days they would occupy the same amount of space. And that knowledge—that I could find balance, that maybe I did need to separate my heart from my head after all—loosened a tension that had seemed to reside in my chest for weeks now." (360).

Lauren's novel is told in the first person, but with alternating points of view, allowing readers into Niall's head so that we can understand his emotions, even if Ruby (and Niall himself) don't. Sherry Thomas, in contrast, confines her story solely to the heroine's first person POV. It's only after you reach the book's ending that you realize just how significant that POV choice is; allowing us only into narrator Evangeline Canterbury shapes the story, and how readers respond to it, un expected ways.

|

| You might be a bit wary, too, if you saw these headlights coming down a deserted road at you... |

|

| Can you really trust a guy who lives in the world's most exclusive NYC apartment building? |

Interestingly, many Goodreads reviewers have responded far more negatively to the emotionally-distant Eva than they did to the emotionally-repressed Niall, even though her emotional issues are conveyed far less directly, far more subtly, than are his. A man in need of training in the ways of emotion and communication (by a woman) is acceptable, even welcome, given how gendered emotional work is in our society. But when a woman is the one who is emotionally closed-off, well, that character is far less comfortable for readers who take it for granted that it is the woman, rather than the man, who is the one responsible for maintaining a romantic relationship's emotional health.

What other emotionally repressed romance characters can you recall from your own reading? Are emotionally-repressed men more common (and/or more beloved) than emotionally distant women?

Photo credits:

Radio City: pixshark

Emotionally distant hearts: Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Tesla headlights: Tesla Motor Club

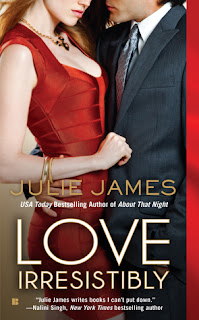

Beautiful Secret

Gallery Books, 2015

The One in My Heart

self-published, 2015