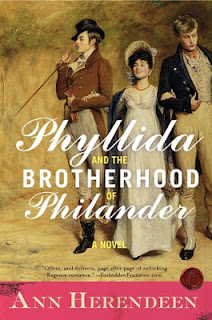

For today's post, I had planned to write about the character arc of the hero in Ann Herendeen's Phyllida and the Brotherhood of Philander. But when I checked out the most recent edition of Journal of Popular Romance Studies, I discovered that Herendeen had already beat me to it by writing an article that analyzes her own book. So instead, I'm going to write instead about another aspect of the book that I admire for feminist reasons: Phyllida's depiction of the multiplicity of ways that one can enact homosexuality.

Herendeen's lighthearted Regency tells the story of Andrew Carrington, heir to an earldom, who considers himself a "sodomite" but decides to marry in order to father an heir. To his surprise, after his marriage of convenience to Gothic novel writer Phyllida Lewis he discovers that bedding his wife has more than its share of charms. But this isn't a "bad man gone straight" story; Andrew doesn't give up his sexual interest in men when he realizes his growing attraction to, and love for, his wife. In fact, Andrew becomes sexually and emotionally involved with another man after his marriage, a man for whom he comes to care as deeply as he does for Phyllida. He has discovered "a new kind of love, in the strangest place" with Phyllida, but he won't give his old love up in exchange for the new (48).

And Phyllida does not ask him to. She agrees to the marriage knowing that Andrew, like the man who introduced them, her neighbor and his friend Sir Frederick Verney, prefers the sexual company of men. She also knows Andrew's reasons for marrying, that sex with him is part of the agreement. But the chance to better her mother and sisters' lives through canny negotiation of the marriage, as well as her own attraction to Andrew ("when he smiled, he looked like the fascinating villains in her books, whom she always ended up falling in love with, try though she might to make them wicked beyond redemption") makes it worth her while (23). She's more than willing to allow Andrew to explore his own sexual proclivities, and even discovers the added benefit that watching her husband with another man is almost as exciting as being with him herself.

Thus the male/female coupling privileged in most romance—Andrew and Phyllida—is transformed into something far from normative—Phyllida and Andrew/Andrew and Matthew. Their relationship does not only challenge heteronormativity (the belief that the only normal sexual relationship is one between a man and a woman), but homonormativity (the adoption of key components of heteronormative belief, such as binary gender norms and monogamous romantic relationships, by LBGTQ individuals and communities*).

Phyllida and Andrew/Andrew and Matthew are not the only challenge to homonormativity in the novel. The founders of "The Brotherhood of Philander," a club for gentlemen sodomites to which Andrew belongs, are part of another tripartite relationship. In this case, however, it was the wife, Lady Isabella Isham, originally the daughter of a tradesman, who "purchased" her man, Lord Isham. The third partner in their relationship, Lord Rupert Archbold, is the linchpin in their relationship, as Lady Isham explains to Phyllida: Marc—Isham that is—and I would roll the dice many an evening. Winner to enjoy the favors of our mutual friend, Rupert. Loser to wait his turn, or hers, although I tried very hard not to lose" (362).

Andrew's other friends, all members of the Brotherhood, construct their sexual relationships in still different ways. Sir Frederick Verney has relationships with different partners at different times (when Andrew asks him if he has a "friend," Verney replies "Not the marrying kind.... Not even with men." [21]). The Honorable Sylvester Monkton, a dandy of the highest order, asserts the same: "The day I take on a partner until death does us part, man or woman, is the day you can lock me up in Bedlam" (513). Sir David Pierce and Mr. George Witherspoon begin the novel as a monogamous couple, devoted to each other for years. Their partnership turns into a trio, however, as David becomes attracted to George's sister, the rather masculine Agatha, and she to him. We even get glimpses of traditional heterosexual relationships: Lord Isham's son, though he has great affection for his father, has a wife and children; Charlotte Swain, a friend of Phyllida's, longs after the very male, very beautiful Alex Bellingham.

As Andrew tells Phyllida after the two are reconciled and admit their love in one ending in a book that has several, "But I do not have to be a gentleman in this bed, just as you do not have to be a lady. So long as we treat each other with kindness, that is all that is required" (481). Protesting the unkindness of heteronormativity and its insistence that there is only one correct way to love others, Herendeen's novel is its own gift of kindness, a gift that blesses multiple ways of loving and being loved.

Photo/illustration credits:

Anti-heteronormativity card: someeecards.com

Homonormative card: urbandictionary.com

Ann Herendeen, Phyllida and the Brotherhood of Philander. New York: Harper, 2008.

Next time on RNFF: Rape in the romance novel

Herendeen's lighthearted Regency tells the story of Andrew Carrington, heir to an earldom, who considers himself a "sodomite" but decides to marry in order to father an heir. To his surprise, after his marriage of convenience to Gothic novel writer Phyllida Lewis he discovers that bedding his wife has more than its share of charms. But this isn't a "bad man gone straight" story; Andrew doesn't give up his sexual interest in men when he realizes his growing attraction to, and love for, his wife. In fact, Andrew becomes sexually and emotionally involved with another man after his marriage, a man for whom he comes to care as deeply as he does for Phyllida. He has discovered "a new kind of love, in the strangest place" with Phyllida, but he won't give his old love up in exchange for the new (48).

And Phyllida does not ask him to. She agrees to the marriage knowing that Andrew, like the man who introduced them, her neighbor and his friend Sir Frederick Verney, prefers the sexual company of men. She also knows Andrew's reasons for marrying, that sex with him is part of the agreement. But the chance to better her mother and sisters' lives through canny negotiation of the marriage, as well as her own attraction to Andrew ("when he smiled, he looked like the fascinating villains in her books, whom she always ended up falling in love with, try though she might to make them wicked beyond redemption") makes it worth her while (23). She's more than willing to allow Andrew to explore his own sexual proclivities, and even discovers the added benefit that watching her husband with another man is almost as exciting as being with him herself.

Thus the male/female coupling privileged in most romance—Andrew and Phyllida—is transformed into something far from normative—Phyllida and Andrew/Andrew and Matthew. Their relationship does not only challenge heteronormativity (the belief that the only normal sexual relationship is one between a man and a woman), but homonormativity (the adoption of key components of heteronormative belief, such as binary gender norms and monogamous romantic relationships, by LBGTQ individuals and communities*).

Phyllida and Andrew/Andrew and Matthew are not the only challenge to homonormativity in the novel. The founders of "The Brotherhood of Philander," a club for gentlemen sodomites to which Andrew belongs, are part of another tripartite relationship. In this case, however, it was the wife, Lady Isabella Isham, originally the daughter of a tradesman, who "purchased" her man, Lord Isham. The third partner in their relationship, Lord Rupert Archbold, is the linchpin in their relationship, as Lady Isham explains to Phyllida: Marc—Isham that is—and I would roll the dice many an evening. Winner to enjoy the favors of our mutual friend, Rupert. Loser to wait his turn, or hers, although I tried very hard not to lose" (362).

Andrew's other friends, all members of the Brotherhood, construct their sexual relationships in still different ways. Sir Frederick Verney has relationships with different partners at different times (when Andrew asks him if he has a "friend," Verney replies "Not the marrying kind.... Not even with men." [21]). The Honorable Sylvester Monkton, a dandy of the highest order, asserts the same: "The day I take on a partner until death does us part, man or woman, is the day you can lock me up in Bedlam" (513). Sir David Pierce and Mr. George Witherspoon begin the novel as a monogamous couple, devoted to each other for years. Their partnership turns into a trio, however, as David becomes attracted to George's sister, the rather masculine Agatha, and she to him. We even get glimpses of traditional heterosexual relationships: Lord Isham's son, though he has great affection for his father, has a wife and children; Charlotte Swain, a friend of Phyllida's, longs after the very male, very beautiful Alex Bellingham.

As Andrew tells Phyllida after the two are reconciled and admit their love in one ending in a book that has several, "But I do not have to be a gentleman in this bed, just as you do not have to be a lady. So long as we treat each other with kindness, that is all that is required" (481). Protesting the unkindness of heteronormativity and its insistence that there is only one correct way to love others, Herendeen's novel is its own gift of kindness, a gift that blesses multiple ways of loving and being loved.

Photo/illustration credits:

Anti-heteronormativity card: someeecards.com

Homonormative card: urbandictionary.com

Ann Herendeen, Phyllida and the Brotherhood of Philander. New York: Harper, 2008.

Next time on RNFF: Rape in the romance novel

Thank you for this -- I'm ordering the book now! What a wonderful blog.

ReplyDeleteYou're very welcome, Bee. Hope you enjoy it!

DeleteThank you so much for posting about this book--it looks like just the sort of thing for me.

ReplyDeleteYou're very welcome, Natalie. Hope you enjoy it!

DeleteAs I read your overview of the book, I started to wonder about reader response. I like what you say here about kindness and how Herendeen suggests the unkindness of heteronormativity, but I wonder how successful a romance could be at such a thing. When I watched Queer as Folk (the American version), I was happy to see that, with Brian and Justin, it challenged heteronormativity as well as the idea that there was one (monogamous-mimicking-heterosexual-marriage) way to love, but I remember some of my friends, including my gay friends, who were upset that Justin and Brian did not marry, that they did not have a "normal" relationship. I wonder, if the goal is to help readers learn to accept new ways of love, can a romance love triangle accomplish it? I have not read this book, but I wonder if I could read this book (as a romance) and not want a monogamous relationship between the hero and the heroine, and, if I want that, can I learn the lesson Herendeen is trying to teach? In "real" life, I am absolutely for different definitions of love, but I could I resist the graviton of narrative (and genre) logic. I don't know...

ReplyDeleteJW: Interesting thoughts! Romance reading definitely trains us to want the monogamous relationship between man and woman (or, with gay romance, between two partners). I'm thinking that I didn't feel that pull when reading PHYLLIDA, though, and your comments make me wonder why.

ReplyDeleteI think it has to do with the way Herendeen portrays jealousy in the novel. I remembering wondering why Phyllida herself didn't feel jealousy, didn't want Andrew all to herself, or why another character who was originally part of a pair but then became the third party in a three-way relationship didn't either. The text never addresses these issues directly, so a reader has to provide his/her own explanation. The one I came up with is that loving men is part of what makes Andrew who he is, and if he were different, Phyllida wouldn't love him.

The only one who seems to feel jealousy is Andrew; he definitely doesn't want to share Phyllida with other men, even as he expects her to remain sexually true to him. Which again seems part of his character.

Perhaps the lack of jealousy allows some readers the space to consider the possibility of relationships other than heterosexual monogamy. Probably not all readers, though. The "success" would depend as much, if not more, on the reader's willingness to consider such a possibility, his or her willingness to consider happiness separate from the "HEA" typical of romance, than on what the text itself does.

When I teach this novel (as I often do), I find that my students rarely have a problem with the triad at the end--except, perhaps, that it's too small. Often they object to Phyllida's not having an additional partner, either male or female, to correspond with Andrew's. She gets her writing (that's part of the opening contract in the novel), and ultimately motherhood as well (at the end of the book), but although she flirts briefly with Matthew (the third in the triad), and they're clearly affectionate, I don't think there's any suggestion that they end up together physically as well.

ReplyDeleteStudents might be jealous on her behalf, that is to say, but it's not that there are too many people in the poly relationship, but too few!

How interesting, Eric, that the book works so successfully to achieve its goals with college-age students. Per JW's query, I wonder if we had a bookclub at an RWA meeting if the reaction would be the same? Would even those heavily invested in one person for one person HEA find this narrative persuasive?

DeleteWell, the book did get championed early on by a couple of romance bloggers--that's part of the story behind how it went from self-published to HarperCollins, I believe. Herendeen sets things up so that you can't really imagine Andrew having an HEA with just one partner. He's monogamous with Phyllida (no other women in the picture), and he he has a "monogamish" relationship with Matthew, so we get a lot of varieties of marriage in the book, too!

DeleteOh, what a lovely blog post! (as Phyllida would say.) E.M. Selinger sent me the link, and this is just what I needed after Hurricane Sandy.

ReplyDeleteThis post almost makes me sorry that I wrote that JPRS article. I would have loved reading what you had to say. *Almost* sorry ;)

Your deep understanding of my story and its characters is very heartening to me, because I realize that portraying a menage a trois as a romance will not necessarily satisfy all readers. I'm delighted that it worked for you. And your discussion with Eric (Selinger) about jealousy--and why Phyllida and other characters don't feel it--is terrific. You answer your own question perfectly. I would add that readers who think that Phyllida should have her own additional partner to make the situation "balanced" or "fair" are missing the point that not everybody *wants* more than one partner. That Andrew has both a male and female partner is an expression of his dual nature; Andrew is not being "unfaithful" to one partner by having the other, and neither Matthew nor Phyllida feels (or should feel) that Andrew is "cheating" when with the other.

In a conversational spirit, I have one little quibble, or perhaps question is a better term. I've noticed that so often in positive discussions of this book that people talk about "homo" and "hetero": normativity, sexuality, and so on. But rarely is the term "bisexual" used. My original subtitle was "A Bisexual Regency Romance," and what I had hoped to do was write a traditional (in style) sexy Regency romance with a bisexual hero. That the story had to end with a menage (or several, as the different arrangements of minor characters formed themselves as I wrote) was a consequence of my refusing to privilege one partner, or one sex, or one sexuality over another.

As you point out, even in the LGBTQ community, there is a tendency toward "homonormativity." And especially for men who have sex with other men (who may or may not identify as bisexual), there is the expectation that this is the more "important" or determining sexuality. Describing a story about a bisexual man as "homoerotic" or as being about "homosexuality" can imply that any "heteroerotic" elements, that is, his relationships with women, are false, either emotionally empty or for show, as they would be for a gay man.

Bisexual people can be said to have both a sexual orientation (bisexual) and a sexual preference. Rarely are their desires exactly equal, fifty-fifty. For someone like Andrew, who is only "slightly bisexual" (as I called a presentation on this book, with apologies to Mary Balogh and her "Slightly" series) it's easy to forget that when he is with that one woman he loves, and once he has come to love her, it is by his choice, just as much as it his choice to be with his male partner.

I offer this only as an observation, and with gratitude to such an insightful discussion of my book. Thank you for reading it, and for reading it so well!

Ann:

DeleteThanks for stopping, by, and for adding your thoughts to the conversation. Bisexuality isn't an area that I've read a lot about, so I appreciate your suggestions for ways to think about Andrew and his sexuality. I remember reading (in a Goodreads review of the book, perhaps?) a comment by a reader who thought the label "bisexual" was inaccurate for Andrew, because he was only attracted to Phyllida, but no other woman. Pointing out that sexual preference for those oriented to bisexuality exists along a continuum helps me to understand why you consider him bisexual.

Are there good books out there that theorize bisexuality that those of us who are undereducated about the topic would do well to read?

That reminds me of the British TV show Bob and Rose from 2001:

Deletehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_%26_Rose

Bob is a gay man who unexpectedly falls in love with a woman (Rose). When his friends and family say he's bisexual, he says "No, I'm a gay man who's in love with this one woman. I'm attracted to men. When I'm out I look at other men, not women."

My feeling about Andrew, as for everyone, is that *he* is the one who must define his sexuality, as each of us must define it for ourselves. That said, I still feel it's important to understand that "bisexual" cannot be restricted to a definition of fifty-fifty, "equal" attraction to "both" sexes (strict gender duality itself being an increasingly outdated concept). The number of people who fit this definition is so small as to render the category meaningless (and is probably one factor in why so few people choose to identify as bisexual). For the concept of bisexuality to have any relevance to real people's lives, it must encompass the ability to feel attraction on any level--emotional, physical--to people of more than one gender. It does not have to mean acting on those desires, merely the ability to feel them.

In 1812, of course, Andrew would continue to be classified as a "sodomite," whether or not he's married to a woman, and whether or not that marriage is based on love, as long as he also has sexual relationships with men. But I find that mode of thinking oppressive to women especially, for reducing us to second-class citizenship in the realms of love and sex, but also to everybody who experiences genuine attachments to people of different genders.

I'd also point out that I show examples of more "mixed" bisexual orientation in some of the minor characters, such as Lord Rupert Archbold and Lord David Pierce (whom you mentioned in your post).

I imagined Rupert as primarily attracted to women, but in love with Marcus Lambert (Lord Isham) since childhood, in a very protective relationship. Rupert is like the reverse of Andrew: attracted to women but in love with this one man.

I imagined Pierce as closest to that "fifty-fifty" idea. I don't state it openly; it's just a part of his nature, in the background. Like most people of any orientation, he is in a monogamous relationship at the start of the story. And like most bisexual people, his relationship defines for outsiders (and readers) his sexuality. Because that relationship is with a man, he's presumed to be gay. When he falls in love with Agatha, while still loving her brother, George, people wrongly assume that his orientation has changed, when in fact it's just a reflection of his natural bisexuality.

Sorry to be so verbose. I'll answer your question about books in a separate entry, as my original answer was too long for the blog.

As to your question about books: I haven't formed these opinions from books, but only from my own experience, and by analyzing my feelings of attraction to men who have sex with men--and then by attending meetings of groups of people who identify as bisexual and hanging out with bisexual people as friends. There are some good books out there, although I'm not sure which ones are better from a theoretical standpoint (I tend not to read stuff like that, because I'm a novelist).

Delete"Getting Bi," edited by Robyn Ochs, is a classic, I think. It's a collection of first-person narratives. Ochs is a well-known and respected voice in the bisexual "movement" or whatever one would call it.

http://www.amazon.com/Getting-Bi-Voices-Bisexuals-Edition/dp/0965388158

"The Bisexual's Guide to the Universe" is another good popular work:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Bisexuals-Guide-Universe-Quips/dp/155583650X/ref=pd_sim_b_2

I think these contemporary popular works are in many ways better than academic theory because they show the way people are thinking *right now,* on a topic that has changed dramatically in a very short time. The "Gay Liberation" movement is relatively recent, and ideas of what bisexuality is--or isn't--have morphed beyond all recognition in a microsecond by comparison.

There's also a listserv called Academic Bi, that, like all listservs, has a mix of crap and useful, serious scholarship on the subject, as well as a way to connect with people doing interesting work. It's a Yahoo group:

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/academic_bi/

And there's the Journal of Biseuxality, a peer-reviwed academic journal:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journal_of_Bisexuality

I write fiction with the hope of creating well-written, intelligent entertainment. All I hoped to accomplish with "Phyllida" was to write a different, beautiful love story that reflects my own desires--and for some readers and reviewers I succeeded.

I never wanted to write something "political," but I find that my chosen theme, what I call "the third perspective," that of the woman who prefers a bisexual husband and a polyamorous marriage, is unavoidably political on some level.

Finally, I just want to thank you again for this excellent blog, so intelligent and such a sophisticated reading of romance fiction.

Thanks, Ann, for taking the time to talk more about bisexuality, and also for your book recommendations. I'm really looking forward to checking them out!

ReplyDeleteYou're welcome! And thank you for allowing me to "talk back" to your blog.

DeleteI realize that my own ideas about bisexuality and my characters' sexuality has changed a lot in the years since I wrote Phyllida (2004). But I still think "bisexual" is a necessary and useful concept for discussions about characters who feel attraction to people of more than one gender.

I'm part of an older generation (in my 50s) that still feels constricted by the binary of "gay" vs. "straight" that dominated the early years of the gay movement. It was all either/or, and there was no place (or so it seemed) for anybody who didn't fit neatly in one of those two little boxes. People who did feel bisexual attractions tended to choose one as the primary orientation and then ignore, deny or suppress the other, so as to be able to identify as 100% gay or straight.

Today's "young people" (boy, does that make me feel old, but I don't how else to express it) are much more fluid in their definitions and thinking. Many people who identify as bisexual say they fall in love with the person, not the gender. My characters, like Andrew, who are slightly bisexual, are similar to me, seeing the attraction toward someone of their own sex as a very different experience from attraction to someone of the opposite. Not better or worse--just different, and that difference is part of the excitement.

Anyway, as you saw in my JPRS piece, I'm writing as much about issues of social class as I am about sexuality. As a twenty-first-century American writing stories that take place among upper-class English people of 200 years ago, I've felt as if I was writing in a foreign language. Developing that fluency was a great challenge and a lot of fun.

And the work that you put into developing that fluency is evident in the superb historical feel of PHYLLIDA.

DeleteAre you going to be writing more Regency romance fiction? Or have your interests shifted to fantasy/sci fi?

Thank you! But yes, now that I feel I've achieved a level of fluency, and written a couple of Regency novels that I can be proud of, I need to move on.

DeleteI admire writers who can stay within one genre for a whole career, but, like many other writers, I can't write the same thing over and over. (Perhaps those authors I admire are able to do it because they don't feel as if they're writing "the same thing" every time.)

At any rate, I did go back and improve some of my "Lady Amalie's memoirs," an odd mix of women's fiction and sword-and-sorcery that were the first stories I wrote. But I'm clearly not the kind of author who can sell self-published e-books :)

Right now I'm struggling with what I hope will become my third "really published" novel, and I can only say that it doesn't fit into a genre.

I'll be eager to read it, whatever genre it ends up falling within (or breaking the boundaries of...)

Delete