Feminism has long had a hate relationship with the fairy tale "Beauty and the Beast." From the animal bridegroom folktale, which Frenchwoman Suzanne de Villeneuve drew on for the first written version of "La Belle et La Bête" in 1740, to the most recent film version of B&B by Disney, feminist literary and cultural critics have often written about the not-so-hidden messages, messages encourage girls and women to stay with and even love "beastly" (i.e. abusive) men, that seem inherent in this trope.

Which is why it is such a pleasure to read contemporary novels or stories penned by authors who draw on the trope, but do so with a clear aim of subverting its sexism. My favorite short story of this type has long been Angela Carter's "The Tiger's Bride," from her 1979 collection The Bloody Chamber and Other Adult Tales, in which it is the beauty who embraces the beastly rather than the beast who is transformed into a beauty. And I've enjoyed novel-length B&B and animal bridegroom novel retellings, too, both for young adults (Robin McKinley's Beauty [1978]; S. Jae Jones' Wintersong [2017]) and for adult romance readers (Mary Balogh's Lord Carew's Bride [1995]; Elizabeth Hoyt's To Beguile a Beast [2009]), novels that draw into question some of the central assumptions of the more sexist versions of the B&B trope.

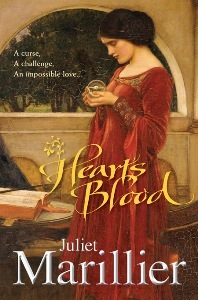

My new favorite, though, might just be Juliet Marillier's 2009 retelling, Heart's Blood.

Set in a 12th century Ireland rife with magic, Marillier's novel opens with heroine Caitrin fleeing toward the beast's home not to save a father, but instead out of grief for one. Berach, a scribe, taught his daughter Caitrin his trade, and the two spent many an hour working together, bent over quill and scroll. But after Berach's sudden death, Caitrin falls into a deep depression, during which distant cousins come and claim her home. Showing a kind face to the town, but an abusive one to Caitrin, Cillian and his mother Ita insult and physically abuse Caitrin until she has internalized all their aspersions:

You're nothing, her dream voice reminded her. You're nobody. Your father shouldn't have filled your head with wild ideas and impossible aspirations.... Bel glad you have responsible kinsfolk to take care of you, Caitrin. It's not as if you've demonstrated an ability to look after yourself since your father died. (12).

When Cillian insists that he and Caitrin wed, however, Caitrin knows she can remain no longer in her once safe home. And so she flees, with only a change of clothes and a small box containing the tools of her trade. And the hopes that she can somehow find her way back to the "old Caitrin, the confident, serene one," rather than the person she has become since her father's death, the person who could not find the power or the will to speak up in the face of Cillian and Ita's abuse (62).

The folk of a far-western settlement Caitrin lands in warn her against accepting the post as scribe at the castle of their local chieftain—"I can't think of one good thing to say about the man, crooked, miserable parasite that he is" (10). But Caitrin, fearful of a pursuing Cillian, won't let herself belief that their stories of a 100-year curse, a horrible lord, a dog large enough to eat a fully grown ram in a single bite, and tiny beings that whispered in traveler's ears and led the off the path are anything more than fearful exaggeration. Caitrin is not coerced into going to the beast's lair to save her father, as in most Beauty and the Beast retellings; she accepts a job willingly, a job which she hopes will help her find herself.

When Caitrin arrives at Whistling Tor, it is to discover that each and every story is true—at least, in its own way. Anluan, the young chieftain, limps, has the use of only one arm, and has a strangely unsymmetrical face. Caitrin's first sight of Anluan clearly places him in the "Beast" role: "There was an odd beauty in his isolation and his sadness, like that of a forlorn prince ensorcelled by a wicked enchantress, or a traveler lost forever in a world far from home." But Caitrin immediately chastises herself for placing him in such a traditional role: "I must stop being so fanciful. Less than a day here, and already I was inventing wild stories about the folk of the house. This was no enchanted prince, just an ill-tempered chieftain with no manners" (45).

Anluan has tragic reasons for his temper, his physical disabilities, and for his lack of social graces, reasons which are gradually revealed to Caitrin over the course of her weeks at the Tor. And though Anluan often falls prey to abrupt bouts of verbal anger, he never acts violently or harms the handful of faithful retainers who remain. What he does lack is hope—the hope that things might change, the hope that the dark cloud under which he has been living might ever abate. And hope is the one thing of which Caitrin will not let go. It is not physical beastliness, then, but despair, which it will be Caitrin's task to banish—not just from Anluan, but from herself.

Caitrin's job at Whistling Tor is to transcribe the documents of Anluan's ancestor Nechtan, searching for a spell which Nechtan apparently could never find. Not a spell to summon dark power, but rather to disperse it: to send the whispering denizens of the forest, the dark legacy Nechtan's willingness to dabble in black sorcery in order to gain power over his rivals, back from whence they were unnaturally summoned. Many of Nechtan's notes are in Latin, a language which Anluan's father did not have the chance to teach him before he took his life when Anluan was only nine, the most recent of a string of early deaths among the chieftain's ancestors.

The task must be completed by the end of summer, Anluan insists, without ever telling Caitrin why. But when rumors of invading Normans begin to swirl, and acts of hurtful vandalism begin to plague the Tor, the search grows ever more urgent. Caitrin is free to leave at any time; she is no prisoner. And she certainly doesn't long to return home, at least, not to a family that no longer exists. But after receiving a threatening emissary from a Norman lord, Anluan insists on sending Caitrin away. Because he doesn't love her? Or because he loves her too much?

(Spoiler: "At last I begin to understand why my father acted as I did. To lose you is to spill my heat's blood. I do not know if I can bear the pain" [315].)

Again, unlike the traditional B&B story, Caitrin's time "home" is not about proving how bad home really is when compared to the luxury of "away." Rather, it is about conquering her particular monster, banishing those who made her feel less than her true self, and remaking her once destroyed family. A task she undertakes not on her own, but with the help of allies she meets during her journey home.

Community and hope, rather than isolation, doubt, and despair, are what Caitrin needs in order to reclaim her birthright—and then, to claim her place by Anluan's side while he faces his own worst fears.

What are your favorite Beauty and the Beast retellings?

Photo credits:

Castle: Geni

Bleeding heart: Moonbeam 13, Deviant Art

Which is why it is such a pleasure to read contemporary novels or stories penned by authors who draw on the trope, but do so with a clear aim of subverting its sexism. My favorite short story of this type has long been Angela Carter's "The Tiger's Bride," from her 1979 collection The Bloody Chamber and Other Adult Tales, in which it is the beauty who embraces the beastly rather than the beast who is transformed into a beauty. And I've enjoyed novel-length B&B and animal bridegroom novel retellings, too, both for young adults (Robin McKinley's Beauty [1978]; S. Jae Jones' Wintersong [2017]) and for adult romance readers (Mary Balogh's Lord Carew's Bride [1995]; Elizabeth Hoyt's To Beguile a Beast [2009]), novels that draw into question some of the central assumptions of the more sexist versions of the B&B trope.

My new favorite, though, might just be Juliet Marillier's 2009 retelling, Heart's Blood.

Set in a 12th century Ireland rife with magic, Marillier's novel opens with heroine Caitrin fleeing toward the beast's home not to save a father, but instead out of grief for one. Berach, a scribe, taught his daughter Caitrin his trade, and the two spent many an hour working together, bent over quill and scroll. But after Berach's sudden death, Caitrin falls into a deep depression, during which distant cousins come and claim her home. Showing a kind face to the town, but an abusive one to Caitrin, Cillian and his mother Ita insult and physically abuse Caitrin until she has internalized all their aspersions:

You're nothing, her dream voice reminded her. You're nobody. Your father shouldn't have filled your head with wild ideas and impossible aspirations.... Bel glad you have responsible kinsfolk to take care of you, Caitrin. It's not as if you've demonstrated an ability to look after yourself since your father died. (12).

When Cillian insists that he and Caitrin wed, however, Caitrin knows she can remain no longer in her once safe home. And so she flees, with only a change of clothes and a small box containing the tools of her trade. And the hopes that she can somehow find her way back to the "old Caitrin, the confident, serene one," rather than the person she has become since her father's death, the person who could not find the power or the will to speak up in the face of Cillian and Ita's abuse (62).

The folk of a far-western settlement Caitrin lands in warn her against accepting the post as scribe at the castle of their local chieftain—"I can't think of one good thing to say about the man, crooked, miserable parasite that he is" (10). But Caitrin, fearful of a pursuing Cillian, won't let herself belief that their stories of a 100-year curse, a horrible lord, a dog large enough to eat a fully grown ram in a single bite, and tiny beings that whispered in traveler's ears and led the off the path are anything more than fearful exaggeration. Caitrin is not coerced into going to the beast's lair to save her father, as in most Beauty and the Beast retellings; she accepts a job willingly, a job which she hopes will help her find herself.

When Caitrin arrives at Whistling Tor, it is to discover that each and every story is true—at least, in its own way. Anluan, the young chieftain, limps, has the use of only one arm, and has a strangely unsymmetrical face. Caitrin's first sight of Anluan clearly places him in the "Beast" role: "There was an odd beauty in his isolation and his sadness, like that of a forlorn prince ensorcelled by a wicked enchantress, or a traveler lost forever in a world far from home." But Caitrin immediately chastises herself for placing him in such a traditional role: "I must stop being so fanciful. Less than a day here, and already I was inventing wild stories about the folk of the house. This was no enchanted prince, just an ill-tempered chieftain with no manners" (45).

Anluan has tragic reasons for his temper, his physical disabilities, and for his lack of social graces, reasons which are gradually revealed to Caitrin over the course of her weeks at the Tor. And though Anluan often falls prey to abrupt bouts of verbal anger, he never acts violently or harms the handful of faithful retainers who remain. What he does lack is hope—the hope that things might change, the hope that the dark cloud under which he has been living might ever abate. And hope is the one thing of which Caitrin will not let go. It is not physical beastliness, then, but despair, which it will be Caitrin's task to banish—not just from Anluan, but from herself.

Caitrin's job at Whistling Tor is to transcribe the documents of Anluan's ancestor Nechtan, searching for a spell which Nechtan apparently could never find. Not a spell to summon dark power, but rather to disperse it: to send the whispering denizens of the forest, the dark legacy Nechtan's willingness to dabble in black sorcery in order to gain power over his rivals, back from whence they were unnaturally summoned. Many of Nechtan's notes are in Latin, a language which Anluan's father did not have the chance to teach him before he took his life when Anluan was only nine, the most recent of a string of early deaths among the chieftain's ancestors.

The task must be completed by the end of summer, Anluan insists, without ever telling Caitrin why. But when rumors of invading Normans begin to swirl, and acts of hurtful vandalism begin to plague the Tor, the search grows ever more urgent. Caitrin is free to leave at any time; she is no prisoner. And she certainly doesn't long to return home, at least, not to a family that no longer exists. But after receiving a threatening emissary from a Norman lord, Anluan insists on sending Caitrin away. Because he doesn't love her? Or because he loves her too much?

(Spoiler: "At last I begin to understand why my father acted as I did. To lose you is to spill my heat's blood. I do not know if I can bear the pain" [315].)

Again, unlike the traditional B&B story, Caitrin's time "home" is not about proving how bad home really is when compared to the luxury of "away." Rather, it is about conquering her particular monster, banishing those who made her feel less than her true self, and remaking her once destroyed family. A task she undertakes not on her own, but with the help of allies she meets during her journey home.

Community and hope, rather than isolation, doubt, and despair, are what Caitrin needs in order to reclaim her birthright—and then, to claim her place by Anluan's side while he faces his own worst fears.

What are your favorite Beauty and the Beast retellings?

Photo credits:

Castle: Geni

Bleeding heart: Moonbeam 13, Deviant Art

Heart's Blood

Tor, 2009

We loved the french movie that came out the last few years. However, I'm not sure how feminist it is. What I loved is that it made sense. There are so many unanswered questions in the Disney version that the french version was a relief.

ReplyDelete