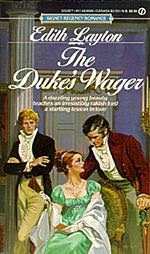

Last month, on the Heroes and Heartbreakers blog, Darlene Marshall wrote a column for lovers of Mary Balogh's historical romances, with recommendations of authors to read "after you've read every Mary Balogh." I'd already read all of Joanna Bourne's books, and most of Jo Beverly's, but I'd only read one by the third author Marshall recommended, Edith Layton. Marshall's description of Layton's The Duke's Wager ("a classic modern Regency which strays beyond the conventions, giving us a questionable hero whose true self is only revealed in small glimpses as the story unfolds")—intrigued me. And so began a month of Layton indulgence.

After reading the first six Signet romances Layton published—The Duke's Wager (1983), The Disdainful Marquis (1983), The Mysterious Heir (1984), Red Jack's Daughter (1984), Lord of Dishonor (1984) and The Abandoned Bride (1985)—I've come to admire Layton's prose style, in particular her skillful use of point of view. Especially in openings of her novels, she often uses a distant narrative point of view to convey the sense of aristocrats being looked upon by the wider world, and being judged by that world:

But when the magnificent carriage bearing the insignia of St. John Basil St. Charles, Marquis of Bessacarr drew up to the curb and a large gentleman alighted, sweeping his impassive stare over them, even the hungriest among them did not press any further forward. Here was a knowing one, they thought, and a hard one, who would not need to dazzle his ladybird with careless largess to strangers. (Kindle Loc 64)

But once her story begins she pulls closer, allowing us inside the heads of her characters.

In spite of the fact that she uses multiple points of view, allowing us access to both her heroes and her heroines' minds, though, I must confess I found her heroes far more interesting, and far more psychologically complex, than the heroines with which they are paired. Layton's heroines may "stray beyond the conventions" of Regency society, but they always do so in plot, not in character. And when they stray, they do so by accident, not by design. For example, Regina of The Duke's Wager mistakenly attends the opera on a night meant only for the demimonde, thus drawing the attention of not just one, but two men who wish to "protect" her, while Catherine of The Disdainful Marquis takes a job as a lady's companion only to discover that her employer "expected her hired companions not to please her, but to please the gentlemen she adored having swarm around her." At heart, though, each young woman is conventional in the Signet Regency way: a virtuous, sexually innocent, good young lady.

Layton's men, though—well, to me at least, they were drawn with far more variety. The Duke's Wager features two rakes, rakes who actually are rakes, one quite openly, the other more in secret:

It was well known that St. John was in the petticoat line, that his doings among these graceless females exceeded that which could be called normal in a man of his position.... There were tales of mistresses, and wild parties and license. But his behavior in the drawing room was impeccable, even if his behavior in other rooms was wide open to speculation. (Kindle Loc 471)

But their reasons for their rakish behavior, as well as their methods for accomplishing their rakish goals, are dramatically different. And because Layton allows us inside both of their heads, as well as inside the head of the current object of their mutual pursuit, readers never know for sure which man will end up winning fair Regina's regard. And readers get to make their own judgments, along with Regina, about the behavior of both men. The best part was that readers get to see how and why one man reforms (at least in part), and why the other does not.

Lord of Dishonor's Christian, Viscount North is a also a rake, but for entirely different reasons than are the gentlemen in Wager. But he, as well as the heroes of the three other books I read, who are more in the upstanding rather than the rakish line, each come across as far more experienced, and thus far more skilled in navigating the social and romantic world, than do their female counterparts. Quite often while reading, I felt as if I were being invited to laugh at the heroines and the mistakes they make because of their inexperience, because I, like the heroes, knew far more about life and love than did the young ladies. And thus that I was being asked to identify more with the heroes than with the heroines.

I'm looking forward to reading further into Layton's Signet oeuvre, to see if her heroes continue to outshine her heroines, and in what ways. In the meantime, though, I'm wondering—are there any readers who prefer romances in which one side of the romantic partnership shines brighter than the other? Or is our current trend toward dual point of view romances make such preferences unlikely?

After reading the first six Signet romances Layton published—The Duke's Wager (1983), The Disdainful Marquis (1983), The Mysterious Heir (1984), Red Jack's Daughter (1984), Lord of Dishonor (1984) and The Abandoned Bride (1985)—I've come to admire Layton's prose style, in particular her skillful use of point of view. Especially in openings of her novels, she often uses a distant narrative point of view to convey the sense of aristocrats being looked upon by the wider world, and being judged by that world:

But when the magnificent carriage bearing the insignia of St. John Basil St. Charles, Marquis of Bessacarr drew up to the curb and a large gentleman alighted, sweeping his impassive stare over them, even the hungriest among them did not press any further forward. Here was a knowing one, they thought, and a hard one, who would not need to dazzle his ladybird with careless largess to strangers. (Kindle Loc 64)

But once her story begins she pulls closer, allowing us inside the heads of her characters.

In spite of the fact that she uses multiple points of view, allowing us access to both her heroes and her heroines' minds, though, I must confess I found her heroes far more interesting, and far more psychologically complex, than the heroines with which they are paired. Layton's heroines may "stray beyond the conventions" of Regency society, but they always do so in plot, not in character. And when they stray, they do so by accident, not by design. For example, Regina of The Duke's Wager mistakenly attends the opera on a night meant only for the demimonde, thus drawing the attention of not just one, but two men who wish to "protect" her, while Catherine of The Disdainful Marquis takes a job as a lady's companion only to discover that her employer "expected her hired companions not to please her, but to please the gentlemen she adored having swarm around her." At heart, though, each young woman is conventional in the Signet Regency way: a virtuous, sexually innocent, good young lady.

Layton's men, though—well, to me at least, they were drawn with far more variety. The Duke's Wager features two rakes, rakes who actually are rakes, one quite openly, the other more in secret:

It was well known that St. John was in the petticoat line, that his doings among these graceless females exceeded that which could be called normal in a man of his position.... There were tales of mistresses, and wild parties and license. But his behavior in the drawing room was impeccable, even if his behavior in other rooms was wide open to speculation. (Kindle Loc 471)

But their reasons for their rakish behavior, as well as their methods for accomplishing their rakish goals, are dramatically different. And because Layton allows us inside both of their heads, as well as inside the head of the current object of their mutual pursuit, readers never know for sure which man will end up winning fair Regina's regard. And readers get to make their own judgments, along with Regina, about the behavior of both men. The best part was that readers get to see how and why one man reforms (at least in part), and why the other does not.

Lord of Dishonor's Christian, Viscount North is a also a rake, but for entirely different reasons than are the gentlemen in Wager. But he, as well as the heroes of the three other books I read, who are more in the upstanding rather than the rakish line, each come across as far more experienced, and thus far more skilled in navigating the social and romantic world, than do their female counterparts. Quite often while reading, I felt as if I were being invited to laugh at the heroines and the mistakes they make because of their inexperience, because I, like the heroes, knew far more about life and love than did the young ladies. And thus that I was being asked to identify more with the heroes than with the heroines.

I'm looking forward to reading further into Layton's Signet oeuvre, to see if her heroes continue to outshine her heroines, and in what ways. In the meantime, though, I'm wondering—are there any readers who prefer romances in which one side of the romantic partnership shines brighter than the other? Or is our current trend toward dual point of view romances make such preferences unlikely?

I found The Duke's Wager really interesting and unusual, as a romance. I didn't exactly "enjoy" it (the men were actual rakes, not the good-natured young men of basically decent morals who happen to employ a mistress who often show up in Regencies with that label) but the prose was so good, and it felt so real and honest.

ReplyDeleteI very much enjoy a male POV in a romance, but very often I feel that I am reading a female fantasy of a male POV (which of course I am... but I don't want to notice it!) instead of actually reading a man's thoughts.

I recently read the Juliana Keyes book "The Good Fight", which is entirely from the POV of the hero. I thought it pretty closely captured what as least feels like a male POV. (It was also unusual in that the hero was more commitment-oriented than the heroine, who was sort of strange and unlikable in ways I hadn't seen in romance before.)

Thanks, anonymous, for stopping by and sharing your thoughts. I actually did enjoy THE DUKE'S WAGER, in large part because the two male protagonists vying for the heroine were actual rakes. I get tired of all the pseudo-rakes who populate regency-era romances...

DeleteWill have to check out THE GOOD FIGHT

My favorite Laytons are _False Angel_ and _To Wed a Stranger_. Both have complex and interesting heroines, which might have something to do with it.

ReplyDeleteCarla Kelly is another who spends a great deal of time in her heroes heads. In fact I realized recently that if Lois McMaster Bujold wrote historical romance, it would read a great deal like Carla Kelly.

I read FALSE ANGEL after you mentioned that it was your fav, Willaful (the one Layton I had read before I started this Layton reading tear). I didn't enjoy it all that much, though. A bit from my Goodreads review: This is one where I felt as if I was meant to laugh at Nell [the heroine] and not always in a kind-spirited manner. And the characterization of Annabelle [the "other woman"] was pretty ugly (enough, already, with describing her "small sharp breasts"!)

DeleteI did enjoy these more than that one, especially LORD OF DISHONOR, THE ABANDONED BRIDE, and THE DUKE'S WAGER. Looking forward to TO WED A STRANGER.

I found Layton's depiction of homosexuality an interesting sub-thread in several of these early books, which seemed pretty unusual for a Signet Regency.

What do you think Bujold and Kelly have in common?

Have you ever got around To Wed a Stranger? I am midway through The Duke's Wager and I know I will want to read more Layton... looking for recommendations! I did read nearly all Balogh!! :)

ReplyDelete